Friday, May 29, 2009

Are Republican Policies Good as Gospel

A Hole in the Gospel

This book belongs in every church library; every pastor needs to read it; and every adult Sunday school class in our country needs to read it and face the facts -- and think of how best to respond. That's my endorsement of this book.Scot goes on to say the central questions the book addresses are:

Does the biblical gospel include justice for the world? Or is justice for the world secondary to the gospel? These are the questions we need to discuss. Where do we define the gospel? From Luke 4:18-19 (gospel of kingdom) or from the message of personal salvation in Romans?I picked it up today!

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

Is this Dispensationalism?

It seems that Paul envisaged the "church" as co-existing in close relation to, but also distinct from historic Israel until such times as Israel may be fully restored. Paul's view of Jews and gentiles is that they remain distinct entities, a distinction that abides, even though all is relativized in Chirst . . . Paul would never confuse Israel and the gentiles, so that although in God's purposes, the two are intertwined and closely related, they remain related but separate entities.Darrell Bock, Progressive Dispensationalism

or

William Campbell, Paul and the Creation of Christian Identity

Sunday, May 24, 2009

Generalist vs. Specialist - SBL Forum

Let us know what you think!

Thursday, May 21, 2009

Preaching in Brisvegas

Difference Between Luther(anism) and Calvin on Justification

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

Old Testament Theologies

Walter Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy

Brevard S. Childs, Old Testament Theology in a Canonical Context

William J. Dumbrell, The Faith of Israel. A Theological Survey of the Old Testament

William Dyrness, Themes in Old Testament Theology

Paul R. House, Old Testament Theology

Walter Eichrodt, Theology of the Old Testament (vols. 1-2)

John Goldingay, Israel's Gospel

Bruce Waltke, An Old Testament Theology

Have I missed any?

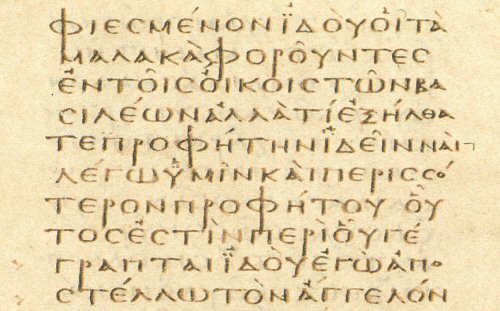

Tormenting Gk Texts Students

What is the book, chapter, and verse for this passage?

What word is missing here compared to the UBS4 version?

Monday, May 18, 2009

Stephen Fowl on Theological Interpretation

For the most part, the various interpretive practices common in the pre-modern period arise from Christian theological convictions. Scripture was seen as God’s gift to the church. Scripture was the central, but not the only, vehicle by which Christians were able to live and worship faithfully before the triune God. It is also the case that faithful living, thinking, and worshipping shaped the ways in which Christians interpreted Scripture. At its best, the diversity and richness of the patterns of reading Scripture in the pre-modern period are governed and directed by Scripture’s role in shaping and being shaped by Christian worship and practice. Ultimately, Scriptural interpretation, worship, and Christian faith and life were all ordered and directed towards helping Christians achieve their proper end in God.

It is important to understand that the difference between modern and pre-modern biblical interpretation is not due to the fact that we are smart and sophisticated while they are ignorant and naïve. Instead, modern biblical study is most clearly distinguished from pre-modern interpretation because of the priority granted to historical concerns over theological ones. Ultimately, if Christians are to interpret Scripture theologically, the first step will involve granting priority to theological concerns. This, however, is to anticipate my conclusion.

On theological interpretation, see also the excellent series of posts by Michael Gorman.

I think theological interpretation is a great thing, and I honestly intend to employ some of it in a forthcoming NT Theology that I'm about to start writing (Lord willing, in a year from now). My only whinge is that more people seem to be talking about theological interpretation than actually doing it!!

Billings on Calvin and Participation

What does it mean to "fear the Lord"?

German Commentaries: Mark

Gnilka's commentary:

1978. Das Evangelium nach Markus. EKKNT. Düsseldorf, Zürich; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Benziger; Neukirchener Verlag.

Pesch's commentary:

1979. Das Markus-Evangelium. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Schnackenburg's two-volume commentary:

1984. Das Evangelium nach Markus. 4th ed. Geistliche Schriftlesung. Düsseldorf: Patmos-Verlag.

Saturday, May 16, 2009

Matthew 1:1: "Son of Abraham" a proposal by Leroy Huizenga

First, Huizenga believes the phrase serves as a title for the whole Gospel and not simply for the genealogy or the infancy narrative or the first major section (1:1—4:16). Given how thoroughly interwoven is the concept of Jesus’ Davidic identity through the whole Gospel, the retrospective look back after reading makes this conclusion clear.

Second, Huizenga makes the important connection between the son of David and son of Abraham. He asserts, essentially, that what is true for the phrase “son of David” must also be true for “son of Abraham”. Thus, one would expect to find a significant thread sown through the Gospel that connects to this title.

These two points are largely well established within the field, but Huizenga then takes a step in a new direction by attempting to show that what Matthew has in mind is not Abraham, so much as Isaac, “the son of Abraham”. The force of his argument is that Matthew’s Gospel contains a robust Isaac typological intiated by this title: “in his first coming, Jesus was not only the Davidic Messiah but also the antitype of Isaac” (108). Central to this typology, for Huizenga, is the Akedah, Isaac’s willing sacrifice of himself. The consequence of which is a Christological category complementary to Davidic Messianism, namely, the sacrificial death of the Messiah. Huizenga writes, “The two categories of Messiah and crucified savior are wrapped up together in the one person, Jesus, with the Isaac typology providing the conceptual category of the atoning death of a martyr” (107). He concludes then the two titles provide a thematic symmetry for Matthew’s Gospel.

Finally, Huizenga’s article briefly points out places in Matthew where allusions and echoes to the Isaac story, and more specifically to the Akedah, have been overlooked. First, pointing out the correspondences between Matthew’s birth narrative and that of Isaac’s in Genesis 17 he summarizes:

The Matthean Jesus and the Isaac of Jewish tradition . . . bear striking resemblance to each other: both are promised children conceived under extraordinary circumstances, beloved Sons who go obediently to their sacrificial deaths at the season of Passover at Jerusalem at the hands of their respective fathers for redemptive purposes (110).Second, Huizenga highlights “precise verbal allusions” to the Septuagint’s Genesis 22—most notably in the Baptism, Transfiguration and Passion narratives.

What do we make of Huizenga’s idea? First, I think he is absolutely correct in his estimation of the programmatic nature of the opening phrase for Matthew’s Gospel. Second, Huizenga has usefully flagged an important and underappreciated aspect of the First Gospel’s cultural context. The evidence for a “robust Isaac typology” is present; and such recognition, at the very least, opens the door wide to fresh readings of particular passages in Matthew. More profoundly, however, the appreciation of an Isaac typology, if we were to agree with Huizenga, would pair it with Davidic Messianism as the central argument of the Gospel. It is this latter point that I still have yet to fully embrace with him.

I am convinced that Matthew has an Isaac typology, but I am less so that the title “son of Abraham” leads by straight line to the Akedah. It is difficult to deny that Mount Moriah would not have been an obvious anti-type for Mount Golgotha in the mind of a Jewish believer in Jesus; however, it is much more difficult to pin the title “son of Abraham” down so specifically. I have wondered, mostly in my own mind and not often aloud, whether or not the titles, “son of David, son of Abraham” were aimed as a barb at the Herodian dynasty; a dynasty that continued into the late first century (Agrippa II). This as least seems possible for two reasons: (1) Jews regularly disparaged Herod as a "half-Jew"; and (2) the intense focus on Herod the Great in the opening scenes of the narrative. More likely, however, the title "son of Abraham" seems most appropriately a reference the fact that as the Davidic Messiah, Israel's vocation, given first to Abraham, comes to its completion. This completion is evinced in the narrative in the so-called Great Commission—a better label I think is the "Great Implication"—likely has Abrahamic echoes.

In any event, Huizenga offers an important observation about Matthew in this good article.

Walter Kaiser and Jewish Exegetical Methods in the NT

Friday, May 15, 2009

Craig Blomberg on N.T. Wright's new book

Wright’s new Justification: God’s Plan and Paul’s Vision (London: SPCK; Downers Grove: IVP, 2009) is an outstanding book. Written in lively, if somewhat polemical style, not encumbered with many footnotes, Wright has here laid out his views with exemplary clarity. In fact, he is affirming all the major Reformation perspectives on justification. The only one he denies is one that was unique to one wing of Calvinism and not even to the entire Calvinist movement. While warmly embracing the representative, substitutionary atonement of Christ through his crucifixion and emphasizing the legal, courtroom context of justification as a metaphor for the declaration of right standing before God not based on anything of our meriting, Wright does deny that Paul, or any other Scriptural author, teaches that the righteousness God imputes to us on the basis of Christ’s cross-work has anything necessarily to do with combining what has been called Jesus’ active obedience (his sinless life) with his passive obedience (his atoning death). And when one looks at the texts often cited in support of such a doctrine (most notably 1 Corinthians 1:30 and 2 Corinthians 5:21), one does indeed look in vain for such a distinction."

Wright’s new Justification: God’s Plan and Paul’s Vision (London: SPCK; Downers Grove: IVP, 2009) is an outstanding book. Written in lively, if somewhat polemical style, not encumbered with many footnotes, Wright has here laid out his views with exemplary clarity. In fact, he is affirming all the major Reformation perspectives on justification. The only one he denies is one that was unique to one wing of Calvinism and not even to the entire Calvinist movement. While warmly embracing the representative, substitutionary atonement of Christ through his crucifixion and emphasizing the legal, courtroom context of justification as a metaphor for the declaration of right standing before God not based on anything of our meriting, Wright does deny that Paul, or any other Scriptural author, teaches that the righteousness God imputes to us on the basis of Christ’s cross-work has anything necessarily to do with combining what has been called Jesus’ active obedience (his sinless life) with his passive obedience (his atoning death). And when one looks at the texts often cited in support of such a doctrine (most notably 1 Corinthians 1:30 and 2 Corinthians 5:21), one does indeed look in vain for such a distinction."Con Campbell on Union with Christ

Thursday, May 14, 2009

D.A. Carson on the Gospel Coalition

Wednesday, May 13, 2009

German Commentaries: Matthew

Joachin Gnilka's two volume commentary:

1986. Das Matthäusevangelium: I. Teil. HTKNT. Freiburg: Herder.

1992. Das Matthäusevangelium: II. Teil. HTKNT. Freiburg: Herder.

Ulrich Luz's four volume commentary:

1990. Das Evangelium nach Matthäus 2. Teilband: Mt 8-17. EKKNT. Düsseldorf, Zürich; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Benziger Verlag; Neukirchener Verlag.

1997. Das Evangelium nach Matthäus 3. Teilband: Mt 18-25. EKKNT. Düsseldorf, Zürich; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Benziger Verlag; Neukirchener Verlag.

2002. Das Evangelium nach Matthäus 4. Teilband: Mt 26-28. EKKNT. Düsseldorf, Zürich; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Benziger Verlag; Neukirchener Verlag.

2002. Das Evangelium nach Matthäus 1. Teilband: Mt 1-7. EKKNT. Düsseldorf, Zürich; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Benziger Verlag; Neukirchener Verlag.

Wolfgang Wiefel's one volume commentary:

1998. Das Evangelium nach Matthäus. THKNT Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt.

Stephen R. Holmes on Evangelical Doctrines of Scriputre

Centrum Paulinium and the Mother of Paul's Theology

Monday, May 11, 2009

NewJoint British-American Ph.D Programme

Saturday, May 09, 2009

Book Notice: J.R. Daniel Kirk - Unlocking Romans

Unlocking Romans: Resurrection and the Justification of God

Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008.

Availabe at Amazon.com

Review: Jesus and the Origins of the Gentile Mission

Friday, May 08, 2009

Today with Calvin

Robin Parry on Jude and 1 Enoch

Andrew Gregory on the non-canonical Gospels

A few comments:

Latest Tyndale Bulletin

Kit Barker

Divine Illocution in Psalm 137: A Critique of Nicholas Wolterstorff's 'Second Hermeneutic'

Hetty Lalleman

Jeremiah, Judgment and Creation

Robert Simons

The Magnificat: Cento, Psalm or Imitatio?

Christopher M. Hays

Hating Wealth and Wives? An Examination of Discipleship Ethics in the Third Gospel

Jake H. O'Connell

Jesus' Resurrection and Collective Hallucinations

Christoph Stenscheke

Reading First Peter in the Context of Early Christian Mission

Jan Henzel

Perseverance Within an Ordo Salutis

Michael P. Theophilos

The Abomination of Desolation in Matthew 24:15

Craig Keener love his Bible

Thursday, May 07, 2009

The Next Big Thing in NT Studies: Gospels

What is more, several things tip me off to look towards Gospels for the future.

1. Gospel of Judas. It looked as if study of the "other" Gospels from Nag Hammadi Codices had teetered out, but the publication of the Gospel of Judas by National Geographic (plus no small amount of sensationalism in the press) certainly reinvigorated the discussion. At SBL in 2007, I felt like I was the only person there who had not written a book on the Gospel of Judas. On the Gospel of Judas see the books by Simon Gathercole, April DeConick, and a good and sane intro is available from Peter M. Head, “The Gospel of Judas and the Qarara Codices: Some Preliminary Observations.” Tyndale Bulletin 58 (2007): 1-23.

2. Move beyond apologetic models. Discussion on the Gospel of Judas did open the subject of what is the difference between the canonical and non-canonical Gospels. It is a good opportunity to break down certain assumptions about the non-canonical Gospels. Not all the non-canonical Gospels were "gnostic" (most students I meet don't really know what gnosticism really is) and not all non-canonical Gospels are "heretical" (e.g. Gospel of Peter, Hebrew versions of Matthew, etc.).

3. Testing old assumptions. Nicholas Perrin's published dissertation on the Gospel of Thomas and Tatian, even if you don't agree with him (see discussion here), goes to show that there is still alot of work to be done in source criticism esp. if you take the time to learn the primary languages that are very rarely learned, i.e. Syriac, Coptic, and Ethiopic. This is better avenue for study than the tiresome hypotheses of a Q-Gos. Thom seedbed for Christian Origins prevalent amongst the Ivy League Gnostics. Likewise, Stephen Carlson's work on the Secret Gospel of Mark has shown how a bit of healthy scepticism can leave many assumptions of scholarship on shakey ground.

4. On publications, there have been a spate of introductions to the non-canonical Gospels and I recommend those by Hans-Joseph Klauck and Paul Foster. There has also been a number of publications of early Gospel Fragments edited by Thomas Kraus, Micahel Kruger, and Tobias Nicklas, Stanley and Wendy Porter, and by Andrew Bernhard which provide a good collection of the primary source texts for us to use.

5. Paul and the Gospels could be a big area too. David C. Sim continues to write a spate of articles articulating the anti-Paulinism of Matthew and I and Joel Willitts are editing a LNTS volume about the relationship of Paul to the canonical Gospels and Gospel of Thomas with an all star cast.

6. Christology of the Gospels. Synoptic Christology will be a new growth industry too. Simon Gathercole's book on Pre-Existence in the Synoptics and C. Kavin Rowe on Lord christology in Luke have begun breaking down the myths of the "low" christology of the Synoptics. The challenge is to situate the christology of the Synoptics in the context of early Christianity but also in relation to views of intermediary figures in second temple Judaism as well as in proximity to Graeco-Roman writings about divine figures. I myself would love to one day do something on the Marcan Jesus and the God of Israel. Though I expect Richard Bauckham will have much to say about that in his forthcoming two volume work on christology and monotheism.

7. Gospel Sources. I think that the field of studies in memory, orality, and texts provides many new exiting vistas for studying the Jesus tradition (see Tom Thatcher's study on John in this regard). Likewise, is it possible to adopt the Farrer-Goulder-Goodacre view on the Synoptic Problem (Luke used Matthew and no Q), but still retain a place for some shared written and oral traditions between Matthew and Luke?

8. The Gospel audiences is still very much uncharted territory. I think Richard Bauckham and co. have taken us beyond the "community" hypothesis in its 20th century form at the height of form and redactional critics, but there are still many hold outs. Bauckham was more careful on this than his critics suppose, he did not deny that the Gospels circulated initially among an immediate audience, only that they were not intended exclusively for that immediate audience. I've had my own dig at the so-called "Marcan Community". In addition, Edward Klink is editing a volume on the Gospel Audiences and it includes my own essay on the audiences of the non-canonical Gospels (Gospel of Thomas, Gospel of Peter, and Jewish Christian Gospels).

9. Many prominent scholars are moving into the field of Gospels research. Richard Hays is now working on echoes of Scripture in the Gospels, Francis Watson is about to start research on the non-canonical Gospels too, Luke Timothy Johnson keeps writing absolutely brilliant essays on the Gospels for various festschriften (see volumes in honour of Robert Morgan and Richard Hays), Simon Gathercole is writing a commentary on the Gospel of Thomas, Andrew Gregory will eventually publish some great work on the Jewish Christian Gospels.

So, if you're looking to do a Ph.D, my advice, start learning either Syriac, Coptic, Ethiopic and find something on the Gospels.

Monday, May 04, 2009

"We believe ... justified by faith" - Peter in Acts and Galatians

-----

What are the Best Hebrew Grammars?

Mark David Futato, Beginning Biblical Hebrew

Page H. Kelley, Biblical Hebrew: An Introductory Grammar

Gary D. Pratico and Miles V. Van Pelt, Basics of Biblical Hebrew Grammar

Allen P. Ross, Introducing Biblical Hebrew

Other ???

Pauline Studies News and Bits

Biggest Issues Facing Evangelicals - Michael Jensen

Phil Ryken responds to Carl Trueman about COE Evangelicals

Well done to Pastor Phil and do read the whole post!