Thursday, September 30, 2010

Raphael Golb Convicted in DSS court case.

Publication from Wheaton N.T.Wright Conference

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

The original Autographs

Monday, September 27, 2010

New Blog: Zurich Connection

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Book Notice: Eric Metaxas: Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy

As people (or it could just be me) we have a tendency to read our hero’s life-story believing that if we stood in their shoes we would have acted or reacted in the same way. I can’t say that about Bonhoeffer. In Eric Metaxas’s new biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy

As people (or it could just be me) we have a tendency to read our hero’s life-story believing that if we stood in their shoes we would have acted or reacted in the same way. I can’t say that about Bonhoeffer. In Eric Metaxas’s new biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, SpyI stood among the shallow-minded Union Theological Seminary students whom Bonhoeffer encountered in New York. At 25 years old, Bonhoeffer was already eons ahead of them both academically and spiritually. He wrote that the Union students:

Talk a blue streak without the slightest substantive foundation and with no evidence of criteria … They are unfamiliar with even the most basic questions. They become intoxicated with liberal and humanistic phrases, laugh at the fundamentalists, and yet basically are not even up to their level (pg. 99).This quote has stuck with me since finishing the book. If I’m honest I find myself talking the same theological blue streak and exhibiting an equal deficiency of depth, insight and self-awareness. I see in myself a lack of maturity and charity and humility and biblical and theological wisdom. Bonhoeffer was the opposite, and as a young man he possessed all of these qualities.

Concerning the book, there are a lot of qualities deserving of comment (narrative style, judicious insight, interaction with sources, organization), but I wish to highlight three.

First, Bonhoeffer was a theologian. His life as a theologian and pastor, calls into question the dichotomy between the pastor’s role to preach and live theology, on the one hand, and the scholar’s role to produce theology on the other. Bonhoeffer was both. Perhaps Bonhoeffer offers a refreshing example of pastor-theologian to a new generation of pastors who wish to construct theology within the context of the church. Bonhoeffer’s work called the church to obedience rather than compromise, and that summons could only be invoked from a deep theological well.

Second, Bonhoeffer embraced ambiguity. Progressing through the narrative, I noticed Bonheoffer’s willingness to accept the murkiness of espionage and conspiracy as discipleship to Jesus. To Bonhoeffer, the ethical implications of faith weren’t separated into simple, clean-cut categories. In other words, killing the Furor was perceived to be God’s will. This provides an ethically uncomfortable question for us to consider (albeit in a comfortable vacuum): What if God’s will is “wrong”, as it’s normally understood? Bonhoeffer was willing to courageously pray and think through these unthinkable difficulties to discern God’s will, and then to put those conclusions into concrete action.

Third, Bonhoeffer was mature. In his relationship with his finance, his decision making, his view of responsibility, his spiritual disciplines, and his ability to endure great suffering that led to death, Bonhoeffer was sustained by Jesus Christ and His body. As you read his letters and books, you interact with a mature person in Jesus Christ.

Metaxas has done an excellent job in bringing us Bonhoeffer’s life-story. We need people like Bonhoeffer, ethically thoughtful, theologically rich, and responsibly Christian. His life challenges complacency, while drawing attention to Jesus Christ, His presence today, and discipleship to Him.

Review by guest contributor: Jameson Ross

Mikeal C. Parsons on Luke's Paul in Luke: Storyteller, Interpreter, Evangelist

I got to know Mikeal Parsons while he was on sabbatical during my Cambridge years. What year now slips me. I found Mikeal to be a great guy and someone who was both engaging and generous. Recently I picked up his book on Luke which is in the Hendrickson series Luke: Storyteller, Interpreter, Evangelist. I really like the series. I have used the two books Warren Carter has writen on Matthew and John for classes I've taught. Parson's book is quite different that Carter's two and is not really ideal for an introduction to the book. However this is not a criticism of the books since Parson's makes it plain in the introduction that he has not intended it to be such a book.

I got to know Mikeal Parsons while he was on sabbatical during my Cambridge years. What year now slips me. I found Mikeal to be a great guy and someone who was both engaging and generous. Recently I picked up his book on Luke which is in the Hendrickson series Luke: Storyteller, Interpreter, Evangelist. I really like the series. I have used the two books Warren Carter has writen on Matthew and John for classes I've taught. Parson's book is quite different that Carter's two and is not really ideal for an introduction to the book. However this is not a criticism of the books since Parson's makes it plain in the introduction that he has not intended it to be such a book.Parsons uses the format of Storyteller, Interpreter, Evangelist to focus his discussion on the Greco-Roman context of Luke's Gospel and Acts. One of its chief concerns is to show the role of ancient rhetoric in Luke's writing. Parson's chapters are informative and insightful. Parson's also has a very interesting chapter on the concept of "friendship" and "physiognomy" in the Greco-Roman world and Luke-Acts.

One of the most important sections of the book as far as I'm concerned is his discussion of the relationship between the Paul of Acts and the Paul of the Pauline Letters. For me these 16 pages (123-39) are worth the price of the book. In this section Parsons critiques the standard view that the Paul of Acts is irreconcilably different than the Paul of the letters.

As an aside, teaching a course on Paul I run into this issue a great deal. As recently as this semester I've had to lecture on this topic because one of the textbooks I'm using for the course Pamela Eisenbaum's Paul Was Not a Christian assumes just such a negative stance toward the Paul of Acts. In her study she excludes Acts as evidence for reconstructing Paul.

Parson's however shows by an unconventional means that Luke's Paul would have appeared familiar to the authorial audience who had known Paul through his letters. Parson writes:

We conclude that the authorial audience who knew Paul through his letters (and probably knew him only through those letters) would have recognized Luke's portrait of Paul as a reliable, though enriched and expanded, presentation of that same Apostle who through his rhetoric, miracles, suffering, adn throught, proclaimed that "God was in Christ reconciling the world unto himself" (p. 139).I would only quibble with Parson's discussion of the Torah in Paul and Acts (pp. 137-8). The discussion is weakened by the assumption that Paul's on-going relationship to the Torah was not motivated by theological conviction but rather expediency as evidenced in Timothy's circumcision (Acts 16:1-3) and Paul's statements in 1 Cor 9:19-23.

Monday, September 20, 2010

Reformed Stuff

Preview of Dale Allison's New Book

N.T. Wright Reads Humpty Dumpty

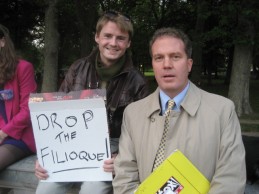

Best Pope Protester Ever

Friday, September 17, 2010

Scripture Memorization

John Dickson - The Christ Files

Projects for 2011 - Gospels and Romans

Forthcoming Paul Books

Paul and the Pauline Letter Collection: Stanley Porter (McMaster Divinity College, Canada)

Paul and Ignatius: Carl Smith (Cedarville University, USA)

Paul and the Letter of Polycarp: Michael Holmes (Bethel University, USA)

Paul and the Epistle of Diognetus: Michael F. Bird (Highland Theological College, UK)

Paul and Marcion: Todd Wilson (George W. Truett Seminary, USA)

Paul and Justin Martyr: Paul Foster (Edinburgh University, UK)

Paul and Valentinian Interpretation: Nick Perrin (wheaton College, USA)

Paul and Judeo-Christians: Joel Willitts (North Park University, USA)

Paul and the Apocryphal Acts: Andrew Gregory (Oxford University, UK)

Paul and Irenaeus: Ben Blackwell (Durham University, UK)

Paul and Tertullian: Andrew Bain (Queensland Theological College, Australia)

Paul and Women: Pauline Hogan (Sir Wilfred Grenfell College, Canada)

The Triumph of Paul or Paulinism in the Second Century?: Mark Elliott (St. Andrews University, UK)

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Review of Introducing Paul by Guy Waters

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

Critical Assessment of Rosner's "Paul and the Law", Part 3

Who is the Christian of whom Rosner speaks?

Perhaps this will appear to you to be a quite unusual question at first. Of course Christians are followers of Jesus Christ both Jew and Gentile you might say. This certainly seems to be the way Rosner is using the term. He states in the conclusion: “although Jews are under the law, believers in Christ are not” (p. 418). This understanding of identity in Paul however is anachronistic and false. It is true that in one place Paul distinguishes Jew, Gentile and the ekklesia of God (1 Cor 10:32). But this type of categorization is exceptional and whatever it might mean, it does not denote the so-called “third race” theology prevalent in the some circles today. Paul’s categories for identity are binary sets: Jew and Greek, male and female, and slave and free (Gal 3:28). For the sake of argument, even if the term "church" were taken as a category for Paul alongside the ethnic distinctions, the term "Christian" was not.

Rosner’s study exhibits this common category error and consequently the thinking does not reflect the complexity of the issue adequately. The result of this weakness is that his conclusion that “a major shift in the way the people of God relate to the law” has occurred for Paul cannot be sustained. While it may be true, the argument in this essay is too weak to establish it.

Let me put my point in a simple a question: Was a Jewish believer in Jesus at the time of Paul a Jew or a Christian?

Monday, September 13, 2010

Critical Assessment of Rosner's "Paul and the Law", Part 2

Before I discuss the essay in any of its details, which I'll do, I want to address a few of the key assumptions Rosner brings to the essay. Now I write this well aware that Brian is reading these posts. So I hope to be irenic in my evaluation and that the points I raise will spur on the conversation. Moreover, I trust that Brian will feel comfortable pointing out errors, when there are such, in my representation of his perspective. I think it is good to write with the awareness that the person along with whom you are thinking is present. And I want to thank Brian for an interesting and thought provoking essay. So here we go.

First, there is an assumption that one can create affirmations of Paul’s thought from non-assertions. Rosner refers to this kind of evidence as “implicit” and treats it on the same level with Paul’s, one might say, “explicit” evidence. However, whatever the “implicit” evidence might offer it is in no way equal in weight to the explicit. The whole essay is an argument from silence. Perhaps in no other situation does ones larger construct of Paul come into play than when one seeks to create a “compelling story” (p. 417) from silence. And for this reason it is just as well that implicit evidence is “largely overlooked in treatments of Paul” (p. 417).

Second, to refer to the implicit evidence as “omissions” is to interpret the evidence, non-evidence really, before actually reading it. To label the so-called silences as “omissions” reveals a position on the question before setting out to answer it. It assumes at least in part that Paul decided to leave out something he might have on other occasions or times included. Anyone who has preached the same message to different audiences will understand that one may “omit” information in one setting that was appropriate in another. However, why should we characterize the non-evidence as omissions? By the way, I’m even having trouble knowing what terms to use to refer to Rosner’s evidence.

One other assumption, although this bleeds over into point of view, is the categories with which this essay functions. Rosner seems boil the groups down to either Jew or Christian and concludes that Paul says one thing about Jews and another about Chrsitians. This bipolar perspective on the constituency of Paul’s communities and early Christianity is in need of critical evaluation. Paul himself stands as one who is BOTH a Jew and a believer in Jesus. Paul’s language about himself in the context of Romans 2, which is the focus of Rosner’s essay, moves easily between Jew (notice the first person references – e.g. 2:5) and Christ believer. These then are not airtight categories of identity. Thus, the bottom line is Rosner’s assessment at the end of the day falls down primarily because of its lack of sophistication with respect to Paul’s understanding, and indeed the situation on the ground in the first century, of Christian identity.

Saturday, September 11, 2010

Critical Assessment of Rosner's "Paul and the Law", Part 1

I will write a few posts in response to Brian Rosner's recent article in JSNT. The title of the article is “Paul and the Law: What he Does not Say” (32.4, pp. 405-19). Here's the first set up post.

Rosner notes three kinds of evidence in Paul’s letters that have a bearing on one’s view of Paul’s understanding of the relationship of the law to the Christian: what Paul says, what Paul does with the law and what Paul does not say about the law. As his starting point, Rosner refers to a quotation from Betz’ Galatians commentary, claiming that Paul never says Christians are to “keep” or “obey” the Torah. He affirms Betz’s idea that Paul carefully distinguishes between the ‘doing’ of the Torah which is not required of Christians and the ‘fulfilling’ of the Torah which is.

The article’s purpose is to use Paul’s silences as a means of ascertaining his view on a Christians relationship to the Torah. He wishes to extend Betz observation. To this end he turns his attention to Romans 2:17-29 as a test case and lists some 10 things Paul says about the Mosaic law and the Jew.

Jews:

- rely on the law (17a)

- boast in the law (v. 23)

- know God’s will through the law (v. 18)

- are educated in the law (v. 18),

- have light, knowledge and truth because of the law (vv. 19-20)

- are to do the law (v. 25)

- (by implication) are to observe the righteous requirements of the law (v. 26)

- keep the law (v. 27);

- occasionally transgress the law (vv. 23, 25, 27)

- possess the (law as) written code (v. 27).

The article sets out to answer on simple question: “Does Paul say the same things of believers in Christ in relation to the law?” (p. 406). The bulk of the essay then takes each item in the list in turn and discusses the silence of Paul on this point with respect to Christians. At times drawing antithetical relationships between what Paul says about a Jew and what he says to a Christian (e.g. Christians rely on Christ not the law).

Rosner concludes his essay thusly, “Paul never says that Christians relate to the law in any of these ways” (p. 417). For him the only reasonable implication from this evidence is “a major shift in the way the people of God relate to the law” has happened (p. 417). “The Law of Moses”, says Rosner, “is much more of a focus for Jews than for Christians and the two groups relate to the law quite differently. The evidence of omission is fully in line with Paul’s perspective that, although Jews are under the law, believers in Christ are not” (pp. 417-18).

Friday, September 10, 2010

Ben Myers on Christian scholarship

Latest Issue of BBR

Thursday, September 09, 2010

Bible College of Victoria

Wednesday, September 08, 2010

Things to Click

James Dunn: NT Theology as "Theologizing"

‘To enter thus into NT theology is to begin to re-experience theology as theologizing, to begin to immerse oneself in the stream of living theology which flowed form Jesus and the reactions to him.’

James D. G. Dunn, ‘Not so much “New Testament Theology” as “New Testament Theologizing”,’ in Aufgabe und Durchführung einer Theologie des Neuen Testaments, eds. Cilliers Breytenback and Jörg Frey (WUNT 205; Tübingen: Mohr/Siebeck, 2007): 227.

Tuesday, September 07, 2010

Zacchaeus and the Rich

Monday, September 06, 2010

Paul Foster: The Gospel of Peter - 2

Paul Foster: The Gospel of Peter - 1

Sunday, September 05, 2010

Christian Sanctification - Indicative but no Imperative?

Synerism?