Showing posts with label Book Review. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Book Review. Show all posts

Thursday, May 05, 2011

Folks are Reading "Introducing Paul"

Over at Academia Church my Introducing Paul is book of the month with some kind comments about how folks have found the book helpful (HT David Byrd).

Monday, May 02, 2011

Love Wins 6

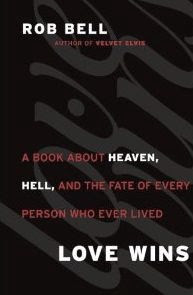

Rob Bell’s fourth chapter in his new book Love Wins: A Book About Heaven, Hell, and the Fate of Every Person Who Ever Lived asks a great question: “Does God Get What God Wants?” This is the sixth installment of a series of posts on the book. In this series, I intend to expose the main lines of argument in each chapter and critically reflect on them. Admittedly, this is not always done systematically as today’s post will reveal.

Rob Bell’s fourth chapter in his new book Love Wins: A Book About Heaven, Hell, and the Fate of Every Person Who Ever Lived asks a great question: “Does God Get What God Wants?” This is the sixth installment of a series of posts on the book. In this series, I intend to expose the main lines of argument in each chapter and critically reflect on them. Admittedly, this is not always done systematically as today’s post will reveal.I think this is probably the best chapter of the book because the argument is tight and the question is significant.

So what do you think?

Does God get what God wants? Is this answer obvious? But perhaps a more important question is: What exactly does God want? Is it presumptuous on our part to state is so simply? Could it be there a number of different answers to the question depending on the point of view or subject?Rob asks: “Have billions of people been created only to spend eternity in conscious punishment and torment, suffering infinitely for the finite sins they committed in the few years they spent on earth?” (102). Great Question. And this really is the central issue of the chapter.

Rob surveys biblical evidence of an inclusive salvation of every person who has ever lived. On reading the list, the conclusion seems obvious: God wants to save everyone. Yet, when one drills down, it becomes a much more complicated picture. Of these complications Rob seems completely unaware. When the Bible speaks of the pilgrimage of the nations to God in the OT, does this mean every person on the earth at the time, let alone every person who's ever lived? There is a difference in the way writers can use the word “all”. “All” can mean: (1) all without exclusion of any one [this is the way Rob takes it] or (2) all without distinction between parties. While not taking the time now to show this exegetically, it is clear from the OT contexts that the second of the two is most often meant. In other words, the prophets are not predicting that every person who ever lived will come to God, but that when God visits in the last days, all the “nations” will come to him. Revelation 5:9 captures this idea in the NT: “for you were slain, and by your blood you ransomed people for God from every tribe and language and people and nation”. Notice that text doesn’t say every person from every tribe, language, people and nation, but representatives, a remnant, of every tribe, language, etc. This is “all with out distinction”. Besides in the very concrete perspective of the OT, there’s no conception of an afterlife salvation. This picture is in purely earthly terms. When God acts in history in bringing salvation, this act will be inclusive of a remnant of people of every nation not only the remnant of Israel.

Now for the sake of argument, it may be true that God will save everyone, but that is not the point of these passages. It seems to me that if one wishes to conclude that God will save all without exception, this is a deductive conclusion because no biblical passage teaches this explicitly. One needs to theologize to this conclusion. This is not a criticism, we do this on plenty of important issues (e.g. Trinity), but it is not specifically stated in Scripture. Thus, an argument like Rob’s doesn’t hold up to scrutiny because his evidence doesn’t actually support the claim. This by the way, goes for the NT evidence as well. Did Jesus and Peter and Paul and James and John believe that every person that ever lived would be saved in the end? Does Jesus’ statement in Matt 19:28 and Peter’s in Acts 3 and Paul’s in Col 1 mean that every person who ever lived will be saved? Again this theological claim may be right, but not based on the evidence given.

God doesn’t get what he wants in salvation from a biblical perspective, only if you define what he wants wrongly. God’s aims are universal, yes cosmic. God’s intentions are inclusive; yes they will reach every nation. And yes, God attains his universal aims and his inclusive intentions.

In order to answer the apparent issue of between God’s universal salvation purposes and the traditional doctrine of hell, Rob lists five options for understanding how to reconcile this contradiction. The options range from the traditional evangelical view, to extreme universalism. Rob maintains that all five of these are comfortably within “orthodoxy”: “Serious, orthodox followers of Jesus have answered these questions in a number of different ways”? (109) This conclusion is of course questionable as I've stated elsewhere since it includes the word "orthodox", although it is true that "serious followers of Jesus" have believed these things and one's view on this question does not make or break one's Christian identity.

Any reader will be able to discern that it’s the fifth option (universalism) that Rob likes best and is most convinced by, although others seem to at least be amicable to him. You even think that the fifth option is what he opts for. But before you can feel that you have got him pegged, he pulls back from that fifth choice in the subsequent paragraphs (pgs 113-17). Rob does not appear to be a universalist because for him human freedom trumps even God’s unrelenting love. But as it turns out, this circumstance is not contrary to what God wants because God wants to love. God’s love has consequences. Love wins, but it doesn’t mean that hell will ultimately be evacuated. Rob may hope for this and surely does, but he’s apparently a realist. Rob says, “Love demands freedom. It always has, and it always will. We are free to resist, reject, and rebel against God’s ways for us. We can have all the hell we want" (113).

In the final analysis according to Rob the question of the chapter “Does God get what he wants?” while a good, interesting and important one, is fraught with speculation about the future. It is no doubt true that God gets what he wants; the precise manner of it is concealed. However, there is a question that he thinks is much easier to answer and no less important. The question: “Do we get what we want?” To that question the answer is absolutely yes. Yes we get what we want, because “God is that loving” (117). So as C.S. Lewis said, there are two kinds of people in the world, those who say ‘Thy will be done’ and those who say, ‘My will be done’.

There is a vague sense of justice in the chapter’s conception of restoration, but it is the weakest part of the chapter and Rob’s whole proposal in my view. Rob writes

This is important, because in speaking of the expansive, extraordinary, infinite love of God there is always the danger of neglecting the very real consequences of God’s love, namely God’s desire and intention to see things become everything they were always intended to be. For this to unfold, God must say about a number of acts and to those who would continue to do them, “Not here you won’t” (113).

*

Still this chapter surfaces what I think to be the most significant and thorny question with which traditional evangelicals must deal: the question of the justness of infinite punishment for finite sin. And this is not simply an issue Rob Bell has raised. The idea that the sin we commit in our finite bodies deserves an infinite amount of punishment seems absurd on any definition to a growing number of people. We can pretend that it makes “perfect sense”, as someone has recently remarked [Tim Keller: “I seems perfectly reasonable for an infinite God to punish infinitely” – round table discussion at Gospel Coalition].But simply saying it’s “perfectly logical” does not actually deal with the question. To growing number of people it's just not. While it in fact may be reasonable, the biblical argument needs to be made today in a way that is freshly compelling and grounded in Scripture. I don’t completely know where I am on this and I haven’t thought enough about it to offer anything of a thoughtful cohesive view. I think there are fundamental parameters, however, within which one must work. In spite of arguments to the contrary, biblically the afterlife of the unrighteous is:

(1) eternal—final and unalterable,

(2) conscious—there is a person, mind and body, and

(3) retributive—there’s no reformation

The actual working out of these is where things are fuzzy for me. In addition, the extent of the actual punishment in this eternal, conscious and retributive state is also something I continue to mull over.

Recently, Scot McKnight in his book One.Life: Jesus Calls, We Follow

So where are we? I have thought long and hard about hell and have come to a view that modifies the second above: hell is a person’s awareness of being utterly absent, which is what “death after death” means, but yet in the presence of God, like C. S. Lewis’ wraiths yearning to be observed and present but deeply aware that they have declined both options. I am unconvinced that annihilation fully answers all that Jesus says, but I also believe that the second view doesn’t contain enough mercy and grace (165).I can’t say I’m convinced by his view. What’s more, I have not rejected the idea, as Scot seems to have, of infinite punishment on the basis of it being unjust. Yet, Scot exhibits the kind of fresh thinking on the question that I think is beneficial. I think we need to go back to the Bible and present its view of ultimate punishment of the wicked in a convincing well-argued manner. Simply appealing to the old argument of an infinite God who, because of his infiniteness, punishes infinitely is not adequate.

For earlier posts for Love Wins see: Post When your wife . . ., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

If you find this post helpful, please share it with others.

Sunday, April 24, 2011

Love Wins 5

I continue my interaction with Rob Bell’s book. Today we come to the third chapter and the topic of hell.

The central point of this chapter is to argue that hell is a real place. But, and most importantly, the reality of hell is not only or even primarily a future place. Hell is present in the world today. Hell is the outcome of people’s choices when they reject “the good and true and beautiful life” God has for them.

Here’s a statement of summary:

Aside from the Bible’s teaching on the subject, do you think this idea of hell is a sufficient answer to humanity’s universal longing for justice?

Now for my quick hits.

1. Hell is not for the victims; what a victim of a hate crime or a rape or genocide has had to endure can be absolutely called “hellish”, but hell is not for them. Hell’s purpose is the final judgment of evil in any form: human and non-human—angels and people.

2. Jewish people at the time of Jesus, and Jesus himself, had no problem believing in eternal punishment. I suspect that most oppressed people don’t.

3. There is plenty of ancient Jewish evidence about hell that would make the most graphic images of hell in the New Testament look like watercolor paintings. I could give references if you want them.

4. Gehenna, to the best of our knowledge, was not a “trash dump”. There’s not one shred of evidence to support this idea that has become self-evident.

5. In the Bible, restorative punishment, punishment whose purpose is to restore, is generally corporate and only for Israel in the OT. What I mean here is that individuals are not the objects of restorative punishment in the OT. Much is made of Ezekiel’s vision of the restoration of Sodom (Ezek 16:44-58) in the chapter. Rob overreaches to make his point. A careful reading of the passage reveals that Ezekiel is speaking of Sodom corporately. The city will be restored with Samaria and with Jerusalem. In the NT, members of the church are chastised in order that they might be restored. There’s no scenario presented that gives even the hint that the unrighteous suffer divine judgment in order to bring them to faith and salvation. See Romans 1:18-32.

6. As the presence of heaven has broken in to the present the present age in the coming of Jesus, so too has the presence of hell. God’s wrath, indeed, is presently being poured out in the present (Rom 1:18-32). But this is not hell.

7. The warnings of judgment on the lips of Jesus transcend the Jewish War of 68-70 and the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple. I am in no way suggesting that these were not within the scope of the judgment, but they do not exhaust the reality of the judgment Jesus predicted.

8. The interpretation of the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus told in Luke 16 is formative for the teaching on hell espoused in the chapter. Rob's reading just doesn't stand up under scrutiny. You can look it over for yourself. In the parable Jesus is teaching that deeds of mercy or lack there of in this life are determinative for the life to come. What one does in this life determines where one will spend the life to come and that final state is unalterable.

In addition, a brief word is required on the interpretation of the phrase “aion kolazo” (“eternal punishment”) in Matthew 25:46. First, the word “kolazo”. The term in Matt 25:46 is the noun not the verb, but both are only used twice in the NT (verb Acts 4:21; 2 Pet 2:9; noun 1 Jn 4:18; Matt 25:46). In none of its uses either in the verb or noun form does it speak of “pruning” or does it refer to a restorative punishment. Second, Rob again, as in the chapter on heaven, insists that Jews didn’t have a category for the idea of forever. This is just wrong. Let me show you a passage where the concept of forever is meant in a context of divine punishment: Revelation 20:10 and 14-15.

Another observation about these passages is the assumption that the lake of fire is not only for God’s explicit enemies. Anyone whose name is not written in the “book of life” will suffer the same fate with the devil, the beast and the false prophet. A so-called neutral position (even giving someone the benefit of the doubt) for John is implicit support for God’s enemies. As someone said once, “You’re either with us, or with them”.

Finally, it appears that Hades, hell that is, is not the same thing as the “lake of fire”. If we harmonize Jesus’ parable about the Rich Man and Lazarus in Luke 16 with the teaching of Revelation here, we would have to say that the Rich man who died and was in Hades in his first death, will be thrown into the lake of fire in the “second death”.

For earlier posts for Love Wins see: Post When your wife . . ., 1, 2, 3, 4.

If you find this post helpful, please share it with others.

The central point of this chapter is to argue that hell is a real place. But, and most importantly, the reality of hell is not only or even primarily a future place. Hell is present in the world today. Hell is the outcome of people’s choices when they reject “the good and true and beautiful life” God has for them.

Here’s a statement of summary:

And that’s what we find in Jesus’ teaching about hell—a volatile mixture of images, pictures, and metaphors that describe the very real experiences and consequences of rejecting our God-given goodness and humanity. Something we are all free to do, anytime, anywhere, with anyone (73).Before reading my bullet point comments, think about the idea:

Aside from the Bible’s teaching on the subject, do you think this idea of hell is a sufficient answer to humanity’s universal longing for justice?

Now for my quick hits.

1. Hell is not for the victims; what a victim of a hate crime or a rape or genocide has had to endure can be absolutely called “hellish”, but hell is not for them. Hell’s purpose is the final judgment of evil in any form: human and non-human—angels and people.

2. Jewish people at the time of Jesus, and Jesus himself, had no problem believing in eternal punishment. I suspect that most oppressed people don’t.

3. There is plenty of ancient Jewish evidence about hell that would make the most graphic images of hell in the New Testament look like watercolor paintings. I could give references if you want them.

4. Gehenna, to the best of our knowledge, was not a “trash dump”. There’s not one shred of evidence to support this idea that has become self-evident.

5. In the Bible, restorative punishment, punishment whose purpose is to restore, is generally corporate and only for Israel in the OT. What I mean here is that individuals are not the objects of restorative punishment in the OT. Much is made of Ezekiel’s vision of the restoration of Sodom (Ezek 16:44-58) in the chapter. Rob overreaches to make his point. A careful reading of the passage reveals that Ezekiel is speaking of Sodom corporately. The city will be restored with Samaria and with Jerusalem. In the NT, members of the church are chastised in order that they might be restored. There’s no scenario presented that gives even the hint that the unrighteous suffer divine judgment in order to bring them to faith and salvation. See Romans 1:18-32.

6. As the presence of heaven has broken in to the present the present age in the coming of Jesus, so too has the presence of hell. God’s wrath, indeed, is presently being poured out in the present (Rom 1:18-32). But this is not hell.

7. The warnings of judgment on the lips of Jesus transcend the Jewish War of 68-70 and the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple. I am in no way suggesting that these were not within the scope of the judgment, but they do not exhaust the reality of the judgment Jesus predicted.

8. The interpretation of the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus told in Luke 16 is formative for the teaching on hell espoused in the chapter. Rob's reading just doesn't stand up under scrutiny. You can look it over for yourself. In the parable Jesus is teaching that deeds of mercy or lack there of in this life are determinative for the life to come. What one does in this life determines where one will spend the life to come and that final state is unalterable.

In addition, a brief word is required on the interpretation of the phrase “aion kolazo” (“eternal punishment”) in Matthew 25:46. First, the word “kolazo”. The term in Matt 25:46 is the noun not the verb, but both are only used twice in the NT (verb Acts 4:21; 2 Pet 2:9; noun 1 Jn 4:18; Matt 25:46). In none of its uses either in the verb or noun form does it speak of “pruning” or does it refer to a restorative punishment. Second, Rob again, as in the chapter on heaven, insists that Jews didn’t have a category for the idea of forever. This is just wrong. Let me show you a passage where the concept of forever is meant in a context of divine punishment: Revelation 20:10 and 14-15.

Rev. 20:10These two texts are related and express a vision of the final fate of God’s enemies. In the first text were told that the devil, the beast and the false prophet will be “thrown” into the “lake of burning sulfur” to be “tormented day and night. This torment according to John will be “for ever and ever”. This phrase is created by repeating the word aion twice. It means something like “for ages upon ages”. In this way John is expressing the idea behind our term “forever”. While the term aion may mean a distinct period of time with a beginning and an end, it can be and is used by biblical authors to express an unending period or set of periods.

And the devil, who deceived them, was thrown into the lake of burning sulfur, where the beast and the false prophet had been thrown. They will be tormented day and night for ever and ever.

Rev. 20:14-15

Then death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. The lake of fire is the second death. 15 All whose names were not found written in the book of life were thrown into the lake of fire.

Another observation about these passages is the assumption that the lake of fire is not only for God’s explicit enemies. Anyone whose name is not written in the “book of life” will suffer the same fate with the devil, the beast and the false prophet. A so-called neutral position (even giving someone the benefit of the doubt) for John is implicit support for God’s enemies. As someone said once, “You’re either with us, or with them”.

Finally, it appears that Hades, hell that is, is not the same thing as the “lake of fire”. If we harmonize Jesus’ parable about the Rich Man and Lazarus in Luke 16 with the teaching of Revelation here, we would have to say that the Rich man who died and was in Hades in his first death, will be thrown into the lake of fire in the “second death”.

For earlier posts for Love Wins see: Post When your wife . . ., 1, 2, 3, 4.

If you find this post helpful, please share it with others.

Sunday, April 17, 2011

Jesus and the Eucharist 4

We’ve been working our way through Brant Pitre’s recent book Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist: Unlocking the Secrets of the Last Supper

We’ve been working our way through Brant Pitre’s recent book Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist: Unlocking the Secrets of the Last SupperChapter three presents the subject of the New Passover. You might recall that in his second chapter, the subject of your last post, he made the point that at the time of Jesus many Jews were expecting a “new Exodus”: an end-time deliverance that would outshine the first Exodus out of Egypt. Chapter three builds on this by suggesting that the new Exodus, as with the first one, would be kicked off with a new Passover event, one that would again outshine the first. Why would this be relevant to Jesus and the Eucharist meal? Because Jesus’ last meal with his disciples in the upper room was most likely the Passover meal eaten at the start of the Sabbath on the 14th day of the Jewish Month of Nissan. Brant states,

On that night, Jesus was not just celebrating one more memorial of the exodus from Egypt. Rather, he was establishing a new Passover, the long-awaited Passover of the Messiah. By means of this sacrifice, Jesus would inaugurate the new exodus, which the prophets had foretold and for which the Jewish people had been waiting (49).Brant believes that knowledge of the Jewish background of the Passover both biblically and in the context of first-century Judaism is crucial for understanding the meaning of the Lord’s Supper. He takes his readers on a very brief and readable survey of the details of the Passover meal.

The Passover ceremony involved five steps as outlined in Exodus 12.

Step 1. Choose an unblemished male lamb.At the time of Jesus, a few significant changes to the ceremony had taken place. It should be emphasized when studying Jesus it is not the biblical framing of teaching, but how those teachings were interpreted and practiced in the first century that is most important. Brant notes four relevant alternations.

Step 2. Sacrifice the lamb

Step 3. Spread the blood of the lamb on the home as a “sign” of the sacrifice.

Step 4. Eat the flesh of the lamb with the unleavened bread.

Step 5. Every year, keep a Passover as a “day of remembrance” of the exodus forever.

1. The Passover sacrifice was now made in the temple in Jerusalem. In the Bible the lambs were sacrificed and eaten in the home of the Israelites in Egypt, but at the time of Jesus these two activities were split and the sacrifice was required to be done in the Jerusalem temple by the Levites. The implication is obvious: you could only celebrate the Passover in Jerusalem. This made for a very busy and bloody day of sacrifice at the temple leading up to the Passover meal. Brant points out impression that would have been left on all those who attended the Passover. This was a brutal sacrifice.

2. The Passover lamb was “crucified” in the process of the sacrifice. Brant appeals to a little known tradition that in the process of the sacrifice two stakes were thrust through the lamb which resembled a crucifixion. This element it must be admitted cannot be historically verified to represent the practice of first-century Jews. Still, if it is correct Brant is right to conclude:This an aspect of the Passover in his day that is neither mentioned in the Bible nor part of the modern-day Jewish Seder, but which as the power to shed light on Jesus’ conception of his own fate (64).

3. The Passover at the time of Jesus became a way to participate in the first Passover. The manner of this contemporizing of the event took shape in traditions that accompanied the Passover meal. The Mishnah, a third-century Rabbinic text, tells us that in the midst of the Passover meal, the son would ask the father, “Why is this night different from other nights?”. This tradition is still practiced today in the Seder. The Passover meal was a way for Jews in every generation to participate in the exodus.

4. Jewish traditions that admittedly date much later than the New Testament but might represent views in the air in the first century, link the Passover feast to the coming of the Messiah and the dawn of the age of salvation. “The Messiah comes on Passover night, and God will redeem his people on that same night” (68).

All of this then forms the frame for seeing Jesus and the Passover meal correctly. Brant suggests that the key is to pay attention to the similarities and differences between the Jewish Passover meal, as described in the Jewish sources, and the meal Jesus had with this disciples recorded in the synoptic gospels. The major observation drawn from a comparison is that Jesus alters the Jewish Passover by placing himself at its center, as the sacrificial lamb. Jesus instituted a “new Passover”.

By means of his words over the bread and wine of the Last Supper, Jesus is saying in no uncertain terms, “I am the new Passover lamb of the new Exodus. This is the Passover of the Messiah, and I am the new sacrifice” (72).Now the pay dirt for Brant in all of this is that according to the ancient biblical tradition, the lamb was to be eaten. Central to the Passover ceremony was the consumption of the flesh of the lamb. As Brant puts it, “the sacrifice of the Passover lamb was not completed by its death. It was completed by a meal, by eating the flesh of the lamb that had been slain” (74).

Brant’s interpretation is very interesting and at many points is profound and instructive. He’s done a great service to us to so clearly spell out the Jewish context of the Passover meal and to draw out connections between Jesus’ last meal with his disciples and the practice of the Passover. Even if not all his connections can be validated, understanding the Eucharist as the Passover of the Messiah is no doubt rich in meaning.

There is one thorny historical issue in all of this that should at least be registered. The question of whether the last supper was the actual Passover meal or a meal on the night before Passover is still a scholarly quandary. John’s Gospel, on the one hand, has the meal on the night before the Passover so that Jesus dies at the time of the sacrifices. On the other hand, the Synoptic Gospels clearly have Jesus’ meal as the Passover. The historical issues are nearly intractable. And while hypotheses have been suggested to harmonize the two accounts no one hypothesis has won the day. What one can say, nevertheless, is that Jesus’ death is associated in all the Gospels with the Passover.

For earlier posts see: Jesus and the Eucharist 1, 2, 3.

Saturday, April 16, 2011

Love Wins 4

I’m continuing to work my way through Rob Bell’s book Love Wins: A Book About Heaven, Hell, and the Fate of Every Person Who Ever Lived

I’m continuing to work my way through Rob Bell’s book Love Wins: A Book About Heaven, Hell, and the Fate of Every Person Who Ever LivedIt seems to me that the central issue in this chapter is the misconception that heaven is “somewhere else”. This misguided and unbiblical perspective, according to Rob, is captured graphically in the picture that used to hang in his grandmother’s home. He says the painting tells a story:

So, the dominant question of this chapter is: what is the correct biblical story of heaven? This question then provides a corrective for the two additionally related questions: Where is heaven and what kind of person will get there?

There are a number of points of detail that could be dealt with in this post. As you might expect this is one of the more length chapters in the book. I will make some brief comments about a few things at the end, but am going to focus more attention in this post on Rob’s reading of the story of the “Rich Young Ruler”, which for all intents and purposes, is the center piece of the chapter.

To correct this “mistaken notion” about heaven [I put this phrase in quotes because it’s a quote from Tom Wright’s Simply Christian—Tom’s been asserting for years and it is no doubt where Rob has gotten it--most comprehensively in Surprised by Hope], Rob turns to the gospel’s story of the “Rich Young Ruler” as told in Matthew 19:16-22 (see parallels in Mark 10:17-22 and Luke 18:18-23).

To correct this “mistaken notion” about heaven [I put this phrase in quotes because it’s a quote from Tom Wright’s Simply Christian—Tom’s been asserting for years and it is no doubt where Rob has gotten it--most comprehensively in Surprised by Hope], Rob turns to the gospel’s story of the “Rich Young Ruler” as told in Matthew 19:16-22 (see parallels in Mark 10:17-22 and Luke 18:18-23).

In the story, Rob finds the truth about heaven. When the young man asked Jesus the question, “What good thing must he do to have eternal life?”, he wasn’t asking about how he gets into heaven when he dies. According to Rob, neither this man nor Jesus ever thought about the future in terms of “going to heaven” when you die. Jesus did not come to make it possible for people to a heaven somewhere else.

To validate this contention, Rob springboards off the story of the Rich Young Ruler to teach a lesson on eschatological views (ideas of the end times) in first-century Judaism. He paints a unified picture of how Jews of Jesus’ day thought about the “end of the world”. Drawing on the Old Testament, Jesus’ Scriptures, Rob shows that ancient Jews thought of history in terms of two ages: the present (this) age and the age to come. He points out that the Greek word translated as “eternal” in the phrase “eternal life” (Matt 19:16) can mean more than one thing, but more significantly, he denies that the term can mean what we most often think it means: “forever” (see discussion below). Instead, Rob suggests that the first of these meanings is best captured with a term like “age”, which he defines as “a period of time with a beginning and ending” (32).

Rob’s point in all this discussion is to show more correctly what the young man was asking Jesus. He wasn’t asking to “go to heaven”; rather he was asking, “How do I participate in the New Age?” As Rob summarizes:

Most importantly, however Rob seems to miss the main point of Jesus response which quite rightly is the last word: “follow me” (19:20). It was not a summons simply to sell all he had and give to the poor. Jesus wasn’t primarily going after his “greed” as Rob thinks. Jesus called him ultimately to “follow”. Obedience is ultimate yes, but it’s also Jesus oriented. The man had to follow Jesus and was unwilling to do so, bottom line.

Nevertheless, I think Rob's comment is insightful and profound: “Jesus takes the man’s question about his life then and makes it about the kind of life he’s living now” (41). This is a significant insight. If you don’t follow Jesus now (this presupposes a lifestyle of ultimate obedience), you won’t be with him then. Heaven isn't simply about someday; its a present reality. Jesus does "blur the lines"; he does merge "heaven and earth".

Now very briefly a few more things:

1) The discussion of “eternal”, aionios, has serious problems. Rob wants to deny that the word aionios ever means what we think of “forever”. This is both right and wrong. It is true that ancient Jews would not have had the same notion of forever as we do, but to say that they could not have thought in terms of forever and that they did not use this word to denote that conception is flat out wrong. Also, there is no evidence to support Rob’s idea that aionios means “intense” (see pg 57). No lexicon of the Greek language supports such an understanding.

2) Rob seems to assume in his retelling of the story of the Rich Young Ruler that the man will participate in the eternal life no matter what. The only question is: Of what will his participation consist? As Rob poses the question “How do you make sure you’ll be part of the new thing God is doing? How do you best become the kind of person whom God could entrust with significant responsibility in the age to come?” (40). This is perhaps the assumption behind his erroneous idea that in heaven fire will purify you and make you fit to “handle heaven” (50). Rob wants to argue that Jesus didn't teach about “getting into" heaven or the age to come. Instead Jesus taught about being “transformed, so that we can actually handle heaven”.

I have to say it, this is just nonsense. Jesus, in point of fact, primarily taught on what Rob says he didn’t. Reflecting on the young man’s refusal Jesus even states, “only with difficult will a rich person enter the kingdom of heaven . . . it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God” (19:23-24). They’ll be no flames in heaven making you fit for it. Jesus does not assume that the young man will be there. Jesus makes the distinction between following Jesus in the here and its reward and “inheriting eternal life”, which is simply another way of saying enter, in the here after (19:29). There is a difference between the two. And being in one does not mean you’ll be in the other. But how you live in the one will determine your presence in the other. You'll enter the other by how you live in the present.

3) The discussion of “treasure” and whether treasure is static or dynamic (43-47) is baffling to me. What is ironic is while arguing for a view of heaven rooted in a first-century Jewish mindset, the topic of “treasures in heaven” is untethered from any such rootedness. It seems that Jesus himself promised “static” rewards (19:28).

4) Definition of “heaven”:

Heaven is a complex biblical idea however. There is a heaven that is distinct from the earth. They are not the same place. Right now God is in heaven and at the time of his choosing he’ll turn the eschatological calendar sending Jesus to finish the work. Yet, in the meantime because of Jesus’ resurrection life and the gift of the Spirit in the church, heaven can be enacted in this time and in this place through the work of the church. Where the church steps, heaven’s footprint is left.

This finally brings us to the question of who is in heaven. First, it needs to be said that Jesus does call people to "enter heaven", although we need to define that term appropriately. The story of the Rich Young Ruler itself shows this. Second, the saints in both the Old and New Testament times are in heaven right now. When we die, if we have entrusted ourselves to Jesus [if we follow Jesus], we’ll be in heaven immediately. This however is not the last word and it might not have been what Jesus the the young man were discussing as Rob points out. Heaven will unite with a renewed earth and it’s this harmony that the Bible foresees as the final state, eternal life. Eternal life is both a quality of life (Rob’s point) and a quantity of life (forever).

For earlier posts for Love Wins see: Post When your wife . . ., 1, 2, 3.

If you like this post please share it with others.

It’s a story of movement, from one place to the next, from one realm to another, from death to life, with the cross as the bridge, the way, the hope . . . But the story also tells us something else, something really, really important, something significant about the location. According to the painting, all of this is happening somewhere else . . . I show you this painting because, as surreal as it is, the fundamental story it tells about heaven—that it is somewhere else—is the story that many people know to be the Christian story (23).Rob believes this story is an unbiblical story. And this unbiblical story has led to two errant consequences. First, because of the story of “heaven somewhere else”, questions related to heaven are generally otherworldly. For example, a question like “what will we do in heaven?” is characteristic of this kind of thinking. Second, the story creates an imbalanced emphasis on the question of who’s in heaven and who isn’t.

So, the dominant question of this chapter is: what is the correct biblical story of heaven? This question then provides a corrective for the two additionally related questions: Where is heaven and what kind of person will get there?

There are a number of points of detail that could be dealt with in this post. As you might expect this is one of the more length chapters in the book. I will make some brief comments about a few things at the end, but am going to focus more attention in this post on Rob’s reading of the story of the “Rich Young Ruler”, which for all intents and purposes, is the center piece of the chapter.

To correct this “mistaken notion” about heaven [I put this phrase in quotes because it’s a quote from Tom Wright’s Simply Christian—Tom’s been asserting for years and it is no doubt where Rob has gotten it--most comprehensively in Surprised by Hope], Rob turns to the gospel’s story of the “Rich Young Ruler” as told in Matthew 19:16-22 (see parallels in Mark 10:17-22 and Luke 18:18-23).

To correct this “mistaken notion” about heaven [I put this phrase in quotes because it’s a quote from Tom Wright’s Simply Christian—Tom’s been asserting for years and it is no doubt where Rob has gotten it--most comprehensively in Surprised by Hope], Rob turns to the gospel’s story of the “Rich Young Ruler” as told in Matthew 19:16-22 (see parallels in Mark 10:17-22 and Luke 18:18-23).In the story, Rob finds the truth about heaven. When the young man asked Jesus the question, “What good thing must he do to have eternal life?”, he wasn’t asking about how he gets into heaven when he dies. According to Rob, neither this man nor Jesus ever thought about the future in terms of “going to heaven” when you die. Jesus did not come to make it possible for people to a heaven somewhere else.

To validate this contention, Rob springboards off the story of the Rich Young Ruler to teach a lesson on eschatological views (ideas of the end times) in first-century Judaism. He paints a unified picture of how Jews of Jesus’ day thought about the “end of the world”. Drawing on the Old Testament, Jesus’ Scriptures, Rob shows that ancient Jews thought of history in terms of two ages: the present (this) age and the age to come. He points out that the Greek word translated as “eternal” in the phrase “eternal life” (Matt 19:16) can mean more than one thing, but more significantly, he denies that the term can mean what we most often think it means: “forever” (see discussion below). Instead, Rob suggests that the first of these meanings is best captured with a term like “age”, which he defines as “a period of time with a beginning and ending” (32).

Rob’s point in all this discussion is to show more correctly what the young man was asking Jesus. He wasn’t asking to “go to heaven”; rather he was asking, “How do I participate in the New Age?” As Rob summarizes:

They did not talk about a future life somewhere else, because they anticipated a coming day when the world would be restored, renewed, and redeemed and there would be peace on earth (40).For Rob the point is more a question of how the man participates in this new world God will bring about when he turns the eschatological calendar. Jesus’ answers the man in the way one would expect a Jewish rabbi would: “live the commandments”. “God has shown you how to live. Live that way” (40). The man responds that he does keep the Mosaic commands. As an aside, the man was not saying he was perfect, but that he was living a Torah-observant life within the Covenant God had established with Israel on Sinai. But as Jesus had already been teaching that this kind of obedience was not enough. Here I am alluding to the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7) where Jesus intensifies the Mosaic commandments as the Messianic Teacher of the Torah. The so-called “antithesis” in Matthew 5, where Jesus discussed the commands of the Mosaic Torah with “you’ve heard it said, but I say to you”, could be given the title “Yes and More”. The man then was likely right to ask the “what else must I do” question and it was probably stimulated by Jesus’ own teaching.

Most importantly, however Rob seems to miss the main point of Jesus response which quite rightly is the last word: “follow me” (19:20). It was not a summons simply to sell all he had and give to the poor. Jesus wasn’t primarily going after his “greed” as Rob thinks. Jesus called him ultimately to “follow”. Obedience is ultimate yes, but it’s also Jesus oriented. The man had to follow Jesus and was unwilling to do so, bottom line.

Nevertheless, I think Rob's comment is insightful and profound: “Jesus takes the man’s question about his life then and makes it about the kind of life he’s living now” (41). This is a significant insight. If you don’t follow Jesus now (this presupposes a lifestyle of ultimate obedience), you won’t be with him then. Heaven isn't simply about someday; its a present reality. Jesus does "blur the lines"; he does merge "heaven and earth".

Now very briefly a few more things:

1) The discussion of “eternal”, aionios, has serious problems. Rob wants to deny that the word aionios ever means what we think of “forever”. This is both right and wrong. It is true that ancient Jews would not have had the same notion of forever as we do, but to say that they could not have thought in terms of forever and that they did not use this word to denote that conception is flat out wrong. Also, there is no evidence to support Rob’s idea that aionios means “intense” (see pg 57). No lexicon of the Greek language supports such an understanding.

2) Rob seems to assume in his retelling of the story of the Rich Young Ruler that the man will participate in the eternal life no matter what. The only question is: Of what will his participation consist? As Rob poses the question “How do you make sure you’ll be part of the new thing God is doing? How do you best become the kind of person whom God could entrust with significant responsibility in the age to come?” (40). This is perhaps the assumption behind his erroneous idea that in heaven fire will purify you and make you fit to “handle heaven” (50). Rob wants to argue that Jesus didn't teach about “getting into" heaven or the age to come. Instead Jesus taught about being “transformed, so that we can actually handle heaven”.

I have to say it, this is just nonsense. Jesus, in point of fact, primarily taught on what Rob says he didn’t. Reflecting on the young man’s refusal Jesus even states, “only with difficult will a rich person enter the kingdom of heaven . . . it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God” (19:23-24). They’ll be no flames in heaven making you fit for it. Jesus does not assume that the young man will be there. Jesus makes the distinction between following Jesus in the here and its reward and “inheriting eternal life”, which is simply another way of saying enter, in the here after (19:29). There is a difference between the two. And being in one does not mean you’ll be in the other. But how you live in the one will determine your presence in the other. You'll enter the other by how you live in the present.

3) The discussion of “treasure” and whether treasure is static or dynamic (43-47) is baffling to me. What is ironic is while arguing for a view of heaven rooted in a first-century Jewish mindset, the topic of “treasures in heaven” is untethered from any such rootedness. It seems that Jesus himself promised “static” rewards (19:28).

4) Definition of “heaven”:

Sometimes when Jesus used the word “heaven” he was simply referring to God, using the word as a substitute for the name of God. Second, sometimes when Jesus spoke of heaven, he was referring to the future coming together of heaven and earth in what he and his contemporaries called in the age to come. And then third—and this is where things get really interesting—when Jesus talked about heaven he was talking about our present eternal, intense, real experiences of joy, peace, and love in this life, this side of death and the age to come (58-59).Taking these points in turn. First, only Matthew has Jesus do such a thing; in other words in none of the other Gospels does Jesus replace “God” with the term “Heaven”. This may just have been Mathew’s preference and not much can be assumed than from this about Jesus’ usage. It is true that Matthew uses “heaven” this way. Second, while this is somewhat true. Ancient Jews and early Christians still maintained the distinction between heaven and earth. When saints died they went to heaven from where they will return with Jesus at the end of the age. Collapsing the distinction between heaven and earth to the extend Rob does is unbiblical. If Paul is right “to be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord” then there is a heaven somewhere else at least until the time of Jesus second coming. Jesus did pray that God’s will be done on earth as it is in heaven, but that has yet to occur. Third, this category of heaven is an illusion. Neither Jesus nor any biblical writer defines heaven this way.

*

So what is the final word on Love Wins and heaven? I think it is right to critique the story that the portrait tells with which the chapter opened. I don’t think the picture truthfully represents the biblical story of salvation because the story the picture tells is truncated. I'll say only here that God’s ultimate place for humans is a renewed earth. God is going to make all things new (Rev 21) and the New Jerusalem comes down out of heaven to earth. As I make this point, I am surprised that Rob didn’t discuss Revelation 21-22 in the chapter. It’s absence startling.Heaven is a complex biblical idea however. There is a heaven that is distinct from the earth. They are not the same place. Right now God is in heaven and at the time of his choosing he’ll turn the eschatological calendar sending Jesus to finish the work. Yet, in the meantime because of Jesus’ resurrection life and the gift of the Spirit in the church, heaven can be enacted in this time and in this place through the work of the church. Where the church steps, heaven’s footprint is left.

This finally brings us to the question of who is in heaven. First, it needs to be said that Jesus does call people to "enter heaven", although we need to define that term appropriately. The story of the Rich Young Ruler itself shows this. Second, the saints in both the Old and New Testament times are in heaven right now. When we die, if we have entrusted ourselves to Jesus [if we follow Jesus], we’ll be in heaven immediately. This however is not the last word and it might not have been what Jesus the the young man were discussing as Rob points out. Heaven will unite with a renewed earth and it’s this harmony that the Bible foresees as the final state, eternal life. Eternal life is both a quality of life (Rob’s point) and a quantity of life (forever).

For earlier posts for Love Wins see: Post When your wife . . ., 1, 2, 3.

If you like this post please share it with others.

Sunday, April 10, 2011

Jesus and the Eucharist 3

In his second chapter Brant Pitre, begins to set the stage for his discussion of the Jewish roots of the Eucharist in his recent book. We’ve been doing a series of posts through this interesting and provocative book. Brant begins by asking “What were the Jewish people waiting for?” This indeed is an important question not only for his study, but more generally because the answer to this question will put into context the words and deeds of Jesus more generally that the Eucharist is merely on case in point.

Brant corrects the false notion that the Jewish people were only expecting an earthly, political Messiah, one who would boot out the Romans and rule over a restored political kingdom. It is true that this was an element, perhaps a central one, of first century Jewish expectation, but it is not comprehensive enough an understanding. He comments,

Brant's point is certainly correct and provides a more complete conceptual background for understanding Jesus. If I were to suggest one friendly critique, I would press him on his discussion of the "new promised land" as "not necessarily identical to the earthly land of Israel" (39). While on the surface I can agree with this statement--there is a New Creation element in the New Exodus--I think it is misleading.

The new promise Land will indeed be identical to the earthly Land of Israel, but it includes more. The expectations begin with and are centered on the restoration of the Land (the land promised to the patriarchs, apportioned by Joshua, but never fully acquired) and expand out from there to the entire earth. The expectations don't contain a conception of replacement of the old earthly Land with something else.

Brant corrects the false notion that the Jewish people were only expecting an earthly, political Messiah, one who would boot out the Romans and rule over a restored political kingdom. It is true that this was an element, perhaps a central one, of first century Jewish expectation, but it is not comprehensive enough an understanding. He comments,

While some Jews may have been waiting for a merely military Messiah, this was not necessarily the case for all. According to the Jewish Scriptures and certain ancient Jewish traditions, for others, the hope for the future consisted of much, much more (41).Brant points out that in addition to a political deliverance, the Jewish people were expecting a “new exodus”. In the pattern of the first exodus led by Moses, at the end of the age, God would bring about an even great exodus—God would return the exiles back to the Promised Land from the lands to which they were scattered. In order to do so, God would (1) raise up a “new Moses”, (2) establish a “new covenant”, (3) and build a “new temple”.

It was a hope for the coming Messiah, who would not just be a king, but a prophet and a miracle worker like Moses. It was a hope for the making of a new and everlasting covenant, which would climax in a heavenly banquet where the righteous would see God, and feast on the divine presence. It was the hope for the building of a new Temple, where God would be worshiped forever and ever. Finally, it was a hope for the ingathering of God’s people into the promised land of a world made new (41-42).The New Exodus tradition, and its concomitant elements, that Brant argues is the appropriate background against which to understand Jesus words and deeds generally and in particular the meaning of the Last Supper.

Brant's point is certainly correct and provides a more complete conceptual background for understanding Jesus. If I were to suggest one friendly critique, I would press him on his discussion of the "new promised land" as "not necessarily identical to the earthly land of Israel" (39). While on the surface I can agree with this statement--there is a New Creation element in the New Exodus--I think it is misleading.

The new promise Land will indeed be identical to the earthly Land of Israel, but it includes more. The expectations begin with and are centered on the restoration of the Land (the land promised to the patriarchs, apportioned by Joshua, but never fully acquired) and expand out from there to the entire earth. The expectations don't contain a conception of replacement of the old earthly Land with something else.

Friday, April 08, 2011

Love Wins 3

Chapter one of Love Wins is a stream of consciousness. It is a set of ideas in the form of questions that loosely hold together.

Chapter one of Love Wins is a stream of consciousness. It is a set of ideas in the form of questions that loosely hold together.Reading the chapter I felt like I often do when talking to my 4-year-old daughter. Mary, my budding conversationalist, beads ideas together whose only relationship is that the one idea caused her to think of another. But perhaps that’s the point. Perhaps Rob didn’t intend for the chapter to be read like as a geometric proof. Perhaps the issue then is genre. This chapter is more like poetry than an argument to be dissected or carefully analyzed. Perhaps to treat it as such would be to miss the overall poetic affect. Giving the benefit of the doubt to the author, let's go with this more poetic approach.

What then is the poetic affect? What does it all add up to?

At least two stand out to me. One, the chapter leaves you with the impression that the author is a critical thinker. Someone whose thought hard about this stuff and is in a position to offer more convincing alternatives. Two, the chapter leaves you with the undeniable impression that there is something terribly wrong with conventional evangelical thinking.

What particular areas of evangelical thinking? Based on the lines of questioning I came up with twelve topics:

The thinking behind the questions at points is critical in the best sense of the word. As examples, I point to the important problems of an infinite punishment for finite sin and the population sizes of heaven and hell. I do think these are important subjects that are at least worthy of reconsideration. How should the Bible’s figurative language of end-time judgment be understood? Does the Bible teach that God will punish eternally sin committed in a finite body? Will more people go to hell than heaven? I think there are solid biblical reasons to believe that both of these questions are to be answered in the affirmative, but there are also biblical counter arguments that should be honestly weighed and not ignored.

Also, to the extent that our evangelical telling of the Gospel is reductionistic to the point of making God look like someone with a polarity disorder, that should be redressed.

But on the whole the chapter appears to me be more a pseudo-intellectualism rather than real. The problem of a supposed diversity of NT teaching on the way to salvation which takes several pages of the chapter is a pseudo-problem for example. While appearing quite insightful, it really amounts to nothing. What’s more, several of the lines of questioning Rob traces are caricatures based on the worst stereotypes of evangelical teaching around.

Penetrating and important questions can be found in this chapter. But they aren't the only kind.

Post 1 and Post 2

1. Presumptive epistemological confidenceSo what do we make of these two poetic impressions?

2. Population sizes of heaven and hell

3. Infinite punishment for finite sin

4. The age of accountability and infant mortality

5. Postmortem second chances

6. “Accepting Jesus” / praying the “sinner’s prayer”

7. Heaven somewhere else

8. Perspectives of Jesus

9. Missionary responsibility

10. Monergism/synergism (Is salvation all God or a combination of God and us?)

11. Personal relationship with Jesus

12. Supposed diversity of NT teaching

The thinking behind the questions at points is critical in the best sense of the word. As examples, I point to the important problems of an infinite punishment for finite sin and the population sizes of heaven and hell. I do think these are important subjects that are at least worthy of reconsideration. How should the Bible’s figurative language of end-time judgment be understood? Does the Bible teach that God will punish eternally sin committed in a finite body? Will more people go to hell than heaven? I think there are solid biblical reasons to believe that both of these questions are to be answered in the affirmative, but there are also biblical counter arguments that should be honestly weighed and not ignored.

Also, to the extent that our evangelical telling of the Gospel is reductionistic to the point of making God look like someone with a polarity disorder, that should be redressed.

But on the whole the chapter appears to me be more a pseudo-intellectualism rather than real. The problem of a supposed diversity of NT teaching on the way to salvation which takes several pages of the chapter is a pseudo-problem for example. While appearing quite insightful, it really amounts to nothing. What’s more, several of the lines of questioning Rob traces are caricatures based on the worst stereotypes of evangelical teaching around.

Penetrating and important questions can be found in this chapter. But they aren't the only kind.

Post 1 and Post 2

Sunday, April 03, 2011

Jesus and the Eucharist 2

Brant Pitre has written a very informative and accessible book on the Jewish roots of the Eucharist and this is the second post in a series engaging Brant’s thought-provoking volume.

Brant Pitre has written a very informative and accessible book on the Jewish roots of the Eucharist and this is the second post in a series engaging Brant’s thought-provoking volume.In the first chapter, “The Mystery of the Last Supper”, Brant discusses his primary goal to situate Jesus’ teaching on the Eucharist in its historical setting in order to show that, in spite of its seeming incongruity with Jesus’ own Jewish tradition, his teaching on eating his flesh and drinking his blood (John 6) (Brant takes this passage eucharistically – more on that in ch. 4) was meant literally. Of his purpose he writes:

My goal is to explain how a first-century Jew like Jesus, Paul, or any other of the apostles, could go from believing that drinking any blood—much less human blood—was an abomination before God, to believing that drinking the blood of Jesus was actually necessary for Christians” (18).

Brant wants to take his reader on a journey back to the first-century world of Jesus and the first Jewish believers in Jesus to help us “see things” as they saw them. Brant believes when we use an informed imagination “we will discover that there is much more in common between ancient Judaism and early Christianity”. In the end, Brant will attempt to show that a Catholic view of the Eucharist (Transubstantiation) is consistent with Jesus’ teaching in their first-century Jewish setting.

There are two points of reflection that I wish to make. First, I am not Catholic. I have never believed in Transubstantiation and still don’t. My own view of the Eucharist is probably somewhere between Zwingli and Calvin. Nevertheless there is a great deal to be gained from reading Brant’s engagement with ancient Judaism and the Gospels both on the question of the Eucharist, but also a proper approach to reading the canonical Jesus in his context. Brant has given me a newfound appreciation for the Catholic doctrine. Reading his book I’ve come to see a biblical foundation for the view and while I am not convinced—this is a whole other issue related to conversion for to be convinced would mean a need to convert to Catholicism—on exegetical grounds, I now better understand and respect the view.

Second, in light of my previous post about Love Wins and the question Rob Bell raised about Jesus’ purpose and the meaning of the Jesus story, I think Brant’s discussion of Jesus humanity is instructive. He states,

For anyone interested in exploring the humanity of Jesus—especially the original meaning of his words and actions—a focus on his Jewish identity is absolutely necessary. Jesus was a historical figure, living in a particular time and place. Therefore, any attempt to understand his words and deeds must reckon with the fact that Jesus lived in an ancient Jewish context . . . this means that virtually all of his teachings were directed to a Jewish audience in a Jewish setting (12).

If this is the case, then it seems overly reductionistic to narrow the meaning of Jesus’ story to “love of God for every single one of us”. “Jesus loves me this I know, for the Bible tells me so” is no doubt true, but a childish (I don’t mean this negatively) abbreviation of the Gospel. Jesus did not present his mission or his message in these terms. Brant points to Jesus’ announcement of his mission and message in Luke 4 to show just how Jewish Jesus’ framework was. Here in his hometown as Jesus began to reveal his identity as Messiah he appealed to the Jewish Scriptures, Isaiah 61:1-4 particularly) and announced that the “anointed one” is here. “Jesus proclaimed to his fellow Jews that their long-held hope for the coming of the Messiah had been fulfilled—in him” (12-13).

Saturday, April 02, 2011

Love Wins 2

In the preface, we find three main assertions. First, the Gospel, Jesus’ story, is “first and foremost about the love of God for every single one of us”. This story, according to the book has been “hijacked” by other stories that “Jesus isn’t interested in telling” because “they have nothing to do with what he came to do”. The book makes the claim that there is a “misguided and toxic” idea circulating widely among many, perhaps most, Christians in the world. This idea, this message, according to Rob Bell “subverts the contagious spread of Jesus’ message”. That message:

A select few Christians will spend forever in a peaceful, joyous place called heaven, while the rest of humanity spends forever in torment and punishment in hell with no chance for anything better. Its clearly communicated to many that this belief is a central truth of the Christian faith and to reject it is in essence to reject Jesus.

The book is an attempt to “reclaim” the correct, true plot of the Jesus story.

Second, the kind of faith Jesus invites believers into “doesn’t skirt the big questions about topics like God and Jesus and salvation and judgment and heaven and hell”. H owever, there are some Christian contexts where questions are not welcomed. The book advocates that questions, inquiry and the discussion that it generates is itself divine. Rob states, “There is no question that Jesus cannot handle, no discussion too volatile, no issue too dangerous”.

owever, there are some Christian contexts where questions are not welcomed. The book advocates that questions, inquiry and the discussion that it generates is itself divine. Rob states, “There is no question that Jesus cannot handle, no discussion too volatile, no issue too dangerous”.

Third, nothing in the book has not been taught or believed by many Christians before Rob Bell. The content of the book it is claimed has been taught an “untold number of times”. He contends that the historic, orthodox Christian faith is a “deep, wide, diverse stream that’s been flowing for thousands of years, carrying a staggering variety of voices, perspectives, and experiences”. The book claims to introduce the reader to “the ancient, ongoing discussion surrounding the resurrected Jesus”.

What do we make of these claims three claims?

The first claim represents an issue of colossal importance because if Rob Bell is in fact correct then we indeed need to repent immediately of our misguided and toxic understanding of the Gospel and push restart. We need to reboot our theological hard drives. If we have the Gospel wrong we won’t have much else right. But is Rob right here? Has the Gospel story been hijacked? Does the majority of evangelical Christians in the twenty-first century have the Gospel all wrong? Have most of us totally lost the plot? Have we left behind Jesus’ primary point? Have we somehow misunderstood or twisted the truth of what Jesus came to do? Well, this is a huge question that would require survey of Gospel accounts let alone a wide-ranging study of Gospel presentations today. Neither of which did Love Wins provide. So, it is certainly an overstatement. But it is worth asking don’t you think? It is possible that given our cultural conditioning we have gotten at least parts of the Gospel wrong? Or perhaps we have overly emphasized some aspects and neglected others?

owever, there are some Christian contexts where questions are not welcomed. The book advocates that questions, inquiry and the discussion that it generates is itself divine. Rob states, “There is no question that Jesus cannot handle, no discussion too volatile, no issue too dangerous”.

owever, there are some Christian contexts where questions are not welcomed. The book advocates that questions, inquiry and the discussion that it generates is itself divine. Rob states, “There is no question that Jesus cannot handle, no discussion too volatile, no issue too dangerous”.Third, nothing in the book has not been taught or believed by many Christians before Rob Bell. The content of the book it is claimed has been taught an “untold number of times”. He contends that the historic, orthodox Christian faith is a “deep, wide, diverse stream that’s been flowing for thousands of years, carrying a staggering variety of voices, perspectives, and experiences”. The book claims to introduce the reader to “the ancient, ongoing discussion surrounding the resurrected Jesus”.

What do we make of these claims three claims?

The first claim represents an issue of colossal importance because if Rob Bell is in fact correct then we indeed need to repent immediately of our misguided and toxic understanding of the Gospel and push restart. We need to reboot our theological hard drives. If we have the Gospel wrong we won’t have much else right. But is Rob right here? Has the Gospel story been hijacked? Does the majority of evangelical Christians in the twenty-first century have the Gospel all wrong? Have most of us totally lost the plot? Have we left behind Jesus’ primary point? Have we somehow misunderstood or twisted the truth of what Jesus came to do? Well, this is a huge question that would require survey of Gospel accounts let alone a wide-ranging study of Gospel presentations today. Neither of which did Love Wins provide. So, it is certainly an overstatement. But it is worth asking don’t you think? It is possible that given our cultural conditioning we have gotten at least parts of the Gospel wrong? Or perhaps we have overly emphasized some aspects and neglected others?

While it is not yet altogether clear what Rob thinks is wrong with the typical evangelical Gospel story we can see glimpses of what he is protesting and what he will consequently develop in the book.

| Traditional View |

| Love Wins |

1. A select few will ultimately be saved. |

| 1. Many if not most or all will ultimately be saved. |

2. There’s no second chance after death. |

| 2. There are an innumerable number of chances to be saved in this life and the next. |

3. Heaven is a place somewhere else. |

| 3. Heaven is here not somewhere else. |

4. The central truth of Christianity is about getting out of hell and into heaven. |

| 4. Whatever the central message of Christian faith is, it’s not about getting in and staying out. |

The second claim about the importance of question asking is interesting. And there is indeed some truth in what he’s said in my opinion. I have noticed that some have taken issue with Rob’s questions asserting that they are not questions so much as statements, rhetorical questions. These are not questions Rob is really asking, they say, they are rather questions to stir up controversy, to cause confusion, to create disequilibrium. I can’t say speak to what the motivation is behind the questions. It seems reasonable to suppose I guess that the author is not simply asking questions for the sake of it. He clearly is making a point with the book and is using questions to create something of a need in his reader to receive his answers. Whatever the motivation, I am convinced that many of the questions the book raises are in fact good questions. And many Christians sitting in our churches are secretly asking them, but afraid to raise them publicly. I have a person at my church come to me late last year and confess that they were an evangelical universalist. I suppose they thought I would be a safe ear. While many are not as informed about the issues as this particular Christian, I’d be shocked if we conducted a survey of people in our churches and not many of them were either pluralistic or universalists. There is the official teaching of the church and then there is what the Christians who sit in the pews believe. Often these are two very different things. So applaud the book for raising the issues surrounding heaven and hell and putting them front and center. I think that to assume that there aren’t many people who if they thought about it would be convinced that in the end God’s going to sort it out and a good God will not send most of the world’s population who have ever lived to an eternal conscious punishment.

The third claim is perhaps the least able to stand up under the weight of the evidence not in its favor. It is incontrovertible that there has been a wide range of views with the context of what can loosely be labeled Christianity through the two millennia of its existence. However, it is not accurate by any stretch to call orthodox a view that (1) tends toward universalism, (2) presents a “second-chance” theology, and (3) argues that nothing of what is central to the Gospel story is about “getting in”. This view can claim the label orthodoxy about as much as those found among the Gnostic Gospels. Sure there were so-called Christians used these texts and who thought of them as Christian Scripture, but they were on the very fringes of early Christianity representing only a very small minority.

The third claim is perhaps the least able to stand up under the weight of the evidence not in its favor. It is incontrovertible that there has been a wide range of views with the context of what can loosely be labeled Christianity through the two millennia of its existence. However, it is not accurate by any stretch to call orthodox a view that (1) tends toward universalism, (2) presents a “second-chance” theology, and (3) argues that nothing of what is central to the Gospel story is about “getting in”. This view can claim the label orthodoxy about as much as those found among the Gnostic Gospels. Sure there were so-called Christians used these texts and who thought of them as Christian Scripture, but they were on the very fringes of early Christianity representing only a very small minority.

Monday, March 28, 2011

Jesus and the Eucharist 1

My friend and Catholic New Testament scholar Brant Pitre, for whom I have the greatest respect, has just released an interesting, accessible and important book on the Lord’s Supper (i.e. the Eucharist, for those of us low church folks!). The book is Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist: Unlocking the Secrets of the Last Supper

My friend and Catholic New Testament scholar Brant Pitre, for whom I have the greatest respect, has just released an interesting, accessible and important book on the Lord’s Supper (i.e. the Eucharist, for those of us low church folks!). The book is Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist: Unlocking the Secrets of the Last SupperI grew up a Protestant low church Baptist so my understanding of the Lord’s Supper has always been very Zwingli-ish. In other words, I have understood the Lord’s Supper as primarily memorial. In the Lord’s Supper we “remember” and reflect on the death of Jesus. Brant’s provocative thesis in the book is that the traditional Catholic view of transubstantiation, which believes that the bread and wine in communion are transformed literally into the body and blood of Jesus, is rooted in Jesus’ own teaching and first century Jewish context. The book presses me, and all readers, to consider a fresh Jesus’ teaching on the Eucharist. However, this is more than a book about the Eucharist.

In the book, Brant shows the importance of understanding the Jewish context of Jesus. This, for me, is a lesson nearly as important as his thesis on the Eucharist. I will be reflecting on the book in a series of posts.

Brant begins in this introduction with a somewhat darkly comical but yet poignant story of a pre-martial interview with his soon-to-be wife's family's Baptist pastor over 15 years ago. Upon hearing that Brant was a Catholic, the meeting turned from a pre-marital interview into a theological interrogation. As Brant recounts it, the pastor "grilled me on every single controversial point in the Catholic faith". pulled no punches in his questions of Brant over all things Catholic: Mary, the Canon of Scripture, the Pope and the Eucharist.

On the latter topic, the Eucharist, the pastor asked/asserted "How can Catholics teach that bread and wine actually become Jesus' body and blood? Do you really believe that? It's ridiculous!" Brant reflected on the fact that in the moment he was unable to provide a biblical and theological response. He left the meeting devastated. To make matters worse, the pastor said to Brant's fiance that "he has serious concerns about yoking you with an unbeliever".

Brant reflected that this experience was a "major turning point" in his life. He shares that this event became one of the reasons he is a biblical scholar today. Brant writes, "In effect, my exchange with the pastor poured gasoline on the fire of my interest in Scripture". One of the major lessons he learned as he pursued a biblical studies in undergrad, graduate and post-graduate work was this:

If you really want to know who Jesus was and what he was saying and doing, then you need to interpret his words and deeds in their historical context. And that means become familiar with not just ancient Christianity but also with ancient Judaism.

Sunday, March 27, 2011

Love Wins 1

Ok. So what do I think of Rob Bell’s book? What if I say I liked it? What if I say that I didn’t like it? What if I say there were parts that I absolutely agree with and other parts that I could not be more fundamentally in disagreement over? What if I came with anything less than a full condemnation of the book? What if I came down with a full commendation of the book? What if I said this was the best book I’ve read in a long time? What if I said this was the worst book I’ve ever read? Would it matter either way? Or any way?

Ok. So what do I think of Rob Bell’s book? What if I say I liked it? What if I say that I didn’t like it? What if I say there were parts that I absolutely agree with and other parts that I could not be more fundamentally in disagreement over? What if I came with anything less than a full condemnation of the book? What if I came down with a full commendation of the book? What if I said this was the best book I’ve read in a long time? What if I said this was the worst book I’ve ever read? Would it matter either way? Or any way?Decisions about the book, about Rob, have been rendered and sides have been taken. Some have been generous in their disagreement, some vicious in their attack. A few have found it to be a refreshingly positive message. In writing a review of such a provocative book, one puts oneself in a position to get shot at from several directions. Well so be it.

I intend to write a series of posts reflecting on the substantive chapters of the book. My intention is that it serve as something of a “reading guide” for those who may wish to read it, but don’t feel they are in a position to think about it critically and theologically.

I don’t at all think this book is an especially important book on the subject. I think in fact that this will be little more than a “flash in the pan”. But the book has received a tremendous amount of buzz and I have found that people want to read it and talk about it. I think this is a great opportunity to take seriously the views offered here and engage them. I think this has at least two benefits: (1) the topic of heaven and hell and the salvation are extremely important--perhaps the most important topics in the Bible; and (2) such topics deserve attention and rigorous thinking. Again, this book is not important, but the topic and discussion is. To the extent that Love Wins has raised the discussion, it is beneficial.

I don’t at all think this book is an especially important book on the subject. I think in fact that this will be little more than a “flash in the pan”. But the book has received a tremendous amount of buzz and I have found that people want to read it and talk about it. I think this is a great opportunity to take seriously the views offered here and engage them. I think this has at least two benefits: (1) the topic of heaven and hell and the salvation are extremely important--perhaps the most important topics in the Bible; and (2) such topics deserve attention and rigorous thinking. Again, this book is not important, but the topic and discussion is. To the extent that Love Wins has raised the discussion, it is beneficial.

I am going to avoid discussing or naming Rob Bell directly in these posts. I think it is more prudent to address the book and the ideas contained therein and not to discuss Rob or to make personal statements about him. There is too much of this going on in my view. Let's talk about the ideas!

I will begin in this post by listing in random order some affirmative statements about the book by way of introduction. This list will serve to show what I think about the book generally.

- I don’t think this book is well written . . . surprisingly. It doesn’t seem to flow well. Sections in the chapters don’t move seamlessly. I found myself at many points asking “how did we go from there to here?” It feels very “cut and paste”.

- The introduction is a confusing barrage of questions and seems to not really lead anywhere.

- It took me 5 hours to read the book carefully.

- I believe there are errors in the interpretation of the biblical texts in this book.

- I don’t think the book roots the discussion enough in Jesus’ first century Jewish context as perhaps ironically as that may sound.