We began working on this project during the 2008 annual meeting of the ETS-SBL meetings in Providence and Boston. At the meetings, we talked about the different features of Hebrews that point to authorship—style, vocabulary, its apparent oral qualities, theological viewpoints and manuscript tradition, among others. We had always thought that a Luke-Paul collaboration was possible and so we set out to examine various strands of evidence to see what direction they might point in. The somewhat recent trend toward understanding Hebrews in an oral context seemed to have some significant implications for authorship. If Hebrews is a speech, then it may have had stenographer (speech recorder). The content and manuscript (external) evidence pointed to Paul while the linguistic and literary (internal) evidence seemed to us to indicate Lukan involvement. This theory seemed to handle the bulk of the evidence presented on this matter, evidence which was often dichotomized into Luke only and Paul only data. But both sets of data, to our mind, seemed significant and neither could be easily side-stepped. We found, then, that a Pauline origin best explained the main content of Hebrews, accounting for elevated style of the document via Luke’s involvement.

2. What is the basic thesis of your chapter on the authorship of Hebrews?

The evidence we examine suggests that Hebrews likely represents a Pauline speech, probably originally delivered in a Diaspora synagogue, that Luke documented in some way during their travels together and which Luke later published as an independent speech to be circulated among house churches in the Jewish-Christian Diaspora. From Acts, there already exists a historical context for Luke’s recording or in some way attaining and publishing Paul’s speeches in a narrative context. Luke remains the only person in the early Church whom we know to have published Paul’s teaching (beyond supposed Paulinists) and particularly his speeches. And certainly by the first century we have a well established tradition within Greco-Roman rhetorical and historiographic stenography (speech recording through the use of a system of shorthand) of narrative (speeches incorporated into a running narrative), compilation (multiple speeches collected and edited in a single publication) and independent (the publication of a single speech) speech circulation by stenographers. Since it can be shown (1) that early Christians pursued parallel practices, particularly Luke and Mark, (2) that Hebrews and Luke-Acts share substantial linguistic affinities and (3) that significant theological-literary affinities exist between Hebrews and Paul, we argue that a solid case for Luke’s independent publication of Hebrews as a Pauline speech can be sustained. We don’t claim to have “solved” the problem of authorship in terms of absolutes or certainties, but we do think that this is the direction that the evidence points most clearly.

3. Could you summarize what it is about Hebrews that indicates that it is Pauline and what suggests that there is a Lucan hand involved?

To begin with, the oral literary setting for the letter, assumed by most these days, in tandem with evidence for Luke documenting Paul’s speeches in Acts is suggestive of a Luke-Paul collaboration in speech publication. Paul clearly delivered speeches on a number of occasions, some of which are documented by none other than Luke. This establishes a firm historical context for a Luke-Paul collaboration, in which Luke would record and publish Paul’s speeches, already existed in the early Church. There are speeches of others in the apostolic circle (esp. Peter) and beyond (e.g. Stephen), but Luke shows a clear preference in his history for documenting Pauline speech material. And we have further precedent for the early Christian documentation of apostolic speeches later converted in the style of the recorder in the Mark-Peter collaboration—at least, if we take Papias’s account seriously, who informs us that Peter functioned as something of a stenographer in the production of Mark’s Gospel. This is significant in light of the fact that Hebrews is the only document in the New Testament thought by many to be a single independently published speech (i.e. sermon, synagogue homily, etc.). If we begin with the contemporary assumption that Hebrews is a speech or sermon of some kind, this opens up new avenues of exploration for the authorship question that seem to us to point toward a Pauline origin with Lukan involvement.

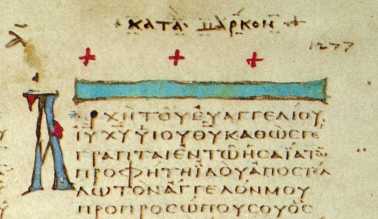

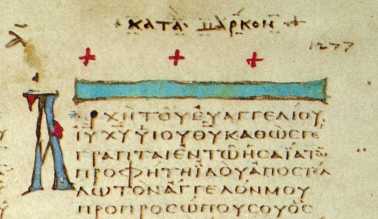

With regard to the external evidence, we should probably expect a fairly high level of the reception history to document a Pauline origin since the scribes, stenographers and historians that circulated such speeches were rarely credited with authorship or if they were, it was merely as a co-author, as we see in many of Paul’s letters. And this is exactly what we find. We immediately think of P46 (200 A.D.), for example, the earliest Pauline canon, which situates Hebrews in the middle of the Pauline corpus. But P46 is only one part of a much wider body of external evidence. A number of further manuscripts favor locating Hebrews immediately after the Pauline letters to the churches and before those written by Paul to individuals, as we find in אB C H I P 0150 0151, a Syrian canon from c. 400 (Mt. Sinain Cod. Syr. 10) and six minuscules from the eleventh century (103). Perhaps such an organization represents the shift in register: from (1) letters to churches to (2) a speech to a church(es) to (3) letters to individuals. The early Eastern fathers also consistently identify Hebrews with Paul. Eusebius records the views of both Clement of Alexandria (Eccl. hist. 6.14.2-3) and Origen (Eccl. hist. 6.25.13) to this effect. When we turn to the primary sources for Origen, the view remains the same. Origen constantly attributes Hebrews to Paul when he cites the document (Princ. 1; 2.3.5; 2.7.7; 3.1.10; 3.2.4; 4.1.13; 4.1.24; Cels. 3.52; 7.29; Ep. Afr. 9). Origen even proposes something like a collaborative hypothesis when he says: “If I gave my opinion, I should say that the thoughts are those of the apostle, but the diction and phraseology are those of some one who remembered the apostolic teachings, and wrote down at his leisure what had been said by his teacher” (Eusebius, Eccel. hist. 6.25.11-14, NPNF2).

We also find it difficult to imagine another person in early Christianity with the background necessary to produce such a composition. We don’t have enough information to make solid judgments regarding the abilities of many proposed authors (Barnabas, Pricilla, Apollos, etc.). A number of Pauline theological features seem evident to us in the Hebrews as well, which many seem to grant. In our chapter, we shore this point up in great detail. One striking feature we observe, for example, is that parallel citation strategies are employed in Hebrews and Paul’s speeches in Acts—for example, the use and exegesis of Pslam 2. A number of other parallel theological features both in Paul’s letters and his speeches in Acts find a direct correlate in Hebrews. In our chapter, we examine these in detail.

In addition to historical considerations, it is the language and style of Hebrews that we find most indicative of Luke’s involvement. Allen goes as far as to suggest that no volume in the New Testament is more similar in its language to Luke-Acts than Hebrews. We lean heavily upon much of his evidence and a collection of additional evidence that we bring to the discussion from our own research in establishing this point.

4. How does a stenographer differ from an amanuensis?

The proposal that perhaps most closely resembles ours is suggested in a footnote by Black when, in attempting to account for the linguistic evidence in Allen’s dissertation on the Lukan authorship of Hebrews, he suggests Luke was perhaps Paul’s amanuensis. The problem with this proposal is that it assumes, contrary to the dominant perspective in scholarship that Hebrews is a letter. Even if this is not the assumption, Black’s idea remains underdeveloped and is not robust enough to in his explanation to make a compelling case. In distinction from Black, we argue that Hebrews is a Pauline speech, independently documented and circulated by Luke, probably based upon his work as a stenographer—a more precise secretarial function related to speech recording rather than the broader domain of amanuensis that Black argues for. J.V. Brown, almost a century ago, advanced a theory similar our proposal when he argued that Paul authored the text but Luke edited and published its final form. Again, we believe a more convincing case can be made through establishing a historical framework in Greco-Roman and early Christian practice in which Luke, as he was accustomed to doing, somehow attained or documented first hand Pauline speech material and published it as an independent speech to be circulated in early Christian communities within the Diaspora. Such a practice is referred to in Greco-Roman historiography and rhetoric as stenography.

5. What do you think of Claire Rothchilds thesis that Hebrews is "Pauline Pseudepigraphy"?

Rothchilds’s thesis (Hebrews as Pseudepigraphon: The History and Significance of the Pauline Attribution of Hebrews [Tubingen: Mohr/Siebeck, 2008 ) remains unconvincing for at least two reasons. First, if someone was attempting to pass Hebrews off as a Pauline letter, then why leave out many of the standard components of Paul’s other letters, such as basic epistolary structure and formulas? It seems to us to be too unique of a document to be an attempted Pauline forgery. If it was a forgery of a Pauline letter, this Paulinist sure did a bad job. But such a situation seems highly unlikely given the composer’s skill and education in literary production. Second, from a very early date the Christian community accepted this letter as an authentic Pauline letter—substantiated by the external evidenced provided above. To overturn this evidence, a significant case would need to be made, a case which Rothchilds fails to deliver on.

6. What are the implications of your thesis for the study of the formation of the NT Canon?

Good question! It seems that the inclusion of the document in a number of primitive canons implies the reception of the document at a very early stage as part of Christianity’s sacred literature. Our theory also helps ground the document’s status in the authorship criterion, which remained a decisive issue in these discussions. We could, then, imagine a reception history similar to Mark’s Gospel under Peter’s authorship or of Luke’s Gospel in light of his connection to Paul.

7. What is Veritas Evangelical Seminary where you teach?

Veritas was recently started here in Temecula, Southern California (just south of Los Angeles and just north of San Diego), where my wife (Amber) and I (Andrew) are from. When Amber and I returned to Temecula from doing Ph.D. studies (New Testament) in the Toronto area at McMaster Divinity College, the president of Veritas, Joe Holden, contacted me to discuss the Dean and Associate Professor of Biblical Studies position there, which was at that time available. He desired to bring more strength and rigor to the biblical studies department at Veritas. I was eventually offered the job and serve in this position now. It certainly is in a great location!

Sean McDonough

Sean McDonough Christ Community Church is a place my wife and I know well. We were on staff here in the mid-to-late 1990's as a youth pastor. I left CCC in 1999 to pursue high education. This pursuit took me back to DTS and to Cambridge, England. In God's providence, however, we're back the far-western suburbs of Chicago and back at CCC. God is very cool.

Christ Community Church is a place my wife and I know well. We were on staff here in the mid-to-late 1990's as a youth pastor. I left CCC in 1999 to pursue high education. This pursuit took me back to DTS and to Cambridge, England. In God's providence, however, we're back the far-western suburbs of Chicago and back at CCC. God is very cool.